West Africa Always Wins

“Is everything OK?”

“It will be. It will be. Everything will be OK” Jean Pierre muttered.

“WAWA,” he said shaking his head. West Africa Always Wins.

The phrase sums up and is symptomatic of the difficulties of travelling in Central Africa. Corruption is endemic and frustrating in the extreme. Hours are spent on dirt roads with boredom and bladders relieved only by occasional stops. Yet for all the hassles, the delays, the protracted and at times painstaking negotiation with fed up and unpaid officials it is all worth it on arrival at Doli Lodge, Dzanga Sangha. Quite simply there are few wildlife experiences that are so overwhelming as Dzanga Sangha. Few places are so totally engrossing.

An oasis in the middle of the rainforest in equatorial Africa, more specifically the Central African Republic, Dzanga Sangha is not an easy part of the world to access. I had arrived in the pulsating capital of Yaoundé a few days earlier to team up with my fellow travellers. There was Rod Cassidy, one of Africa’s leading birders and tour leader extraordinaire; John Maytham, an engaging South African broadcaster; the irrepressible Jean-Pierre, our guide and fixer; and lastly but no means least, the phlegmatic George, our driver from the English-speaking part of Cameroon. Early the next morning we headed west on a logging road, a rich red road that was the arterial highway between the distant and far-flung outposts.

We spent two whole days on the road, passing mats of manioc drying in the sun, collections of huts huddled close to the roadside, children bathing in rivers. We saw signs of the swathe of destruction left by logging. Yellow cassirs lining the road were indicative of forest disturbance. More starkly we came across numerous monkeys, duikers and porcupines for sale: hard evidence of the existence of the illegal bush meat trade. The logging roads have opened up access to the forest and facilitated a huge trade in bush meat or la viande de la forêt as it is known locally. The bush meat trade is quite literally bleeding the forest dry.

It is not just the more common species that are affected by the bush meat trade, even the rare and endangered. In one village we screeched to a halt when we saw a pangolin, a scaly anteater, for sale by the roadside. It was hanging upside down, snare still attached and still alive. After much dilemma and debate we bought it, in order to release it into the forest several miles further down the road. In another village, we were offered a pygmy crocodile for dinner. With its snout bound with twine, it too was alive. We of course declined.

Rod, however, did not decline the offer of mopane worms at one of our roadside stops. Not wishing to lose face I followed suit. As I bit into the crunchy shell of the worm, all thoughts of face vanished. I spat the revolting contents out of my mouth into my clenched fist, much to Rod’s amusement. Its taste was not too bad but the texture was stomach churningly disgusting.

Two days later, standing in front of our local guide, Jean Bernard, the fatigue of travel seemed to lift. Expectation was high as Jean Bernard explained that we had a walk of some fifty minutes through the forest to reach the bai (bai is the local word for a saline or clearing in the forest). He told us that there was a strong chance that we would confront animals. If we met an elephant we were to watch him and follow his actions. If we saw a gorilla we were to kneel down and avoid eye contact. If we saw a leopard we were to gather around him, he said with a grin.

Duly warned we set off into the forest. Surrounded by the submarine darkness of the forest, the dappled light shining through the canopy, everything was heard but unseen. The short-wave squawking of grey parrots overhead, the barked warning of the grey-cheeked mangabey, and the incessant ringing of insects. We crossed a small river, wading through the smell of freshly disturbed stagnant water. Butterflies, in their thousands, flittered and fluttered colourfully around us. Large mounds of elephant dung lay scattered around. The spoor at the side of the stream revealed the presence of several young calves, even very young babies.

“Have you ever seen elephants whilst walking to the mirador?”

“Several times.”

“ Is it dangerous?”

“If the elephants see you it is no problem. But if they have young then it is dangerous.” This did little to reassure me given the tracks that we had just seen.

A scream, a sudden thundering of hooves and crashing of undergrowth made my heart leap. My pride fell when I saw that it was a blue duiker, a small forest antelope barely two feet tall, which was marginally more terrified than I was.

And then we emerged into Dzanga bai, a small clearing in the forest of some two hundred metres by five hundred metres. Less than thirty metres away were a family of elephants. In hushed awe we climbed the wooden steps to the mirador, a raised wooden platform that afforded us a view hitherto seen by only a handful of researchers and wildlife documentary makers. Amazing as documentary footage is it belies the immediacy, the actuality of being there – the phenomenal sounds, the wonderful sights.

There were some thirty elephants in the bai. This number was to fluctuate throughout the day: at midday there were only a handful of elephants in the bai whereas later in the afternoon there were over eighty. Although it was fantastic to see such numbers of forest elephants I was more interested and entertained by simply watching them, noticing and observing detail. The pinkness of one baby’s feet. The lazy swishing of a tail, the uncoordinated flopping of a baby’s trunk, the deliberate spraying of mud by a lone male. Adults raised their trunks, scenting new arrivals, heads were touched, trunks entwined and caressed in greeting. Youngsters, carefree and playful, chased each other around, splashing and sloshing in the water with gay abandon.

Such scenes are perhaps not uncommon across Africa with savannah elephants but much less so with the more skittish forest elephant. It was incredible not only to see such large numbers of forest elephants but also to hear how vocal they were. Trumpeting resounded and resonated around the small clearing as new arrivals entered the saline. The deep rumbling of recognition, the more anxious rumble of distress as a calf looked for Mum – amazingly a female walked out from amongst the crowd to the obvious relief of the distraught calf. The Jurassic roar of a bull as he angrily chases away a mischievous youngster.

The next day we set off to track gorillas, to be precise the western lowland gorilla. Tracking and observing western lowland gorillas is a very different exercise in comparison to the mountain gorillas. The explanation is ecological, that is to say related to the environment. In the equatorial lowland forest, the closed canopy means that grasses are scarce in the undergrowth as light is insufficient, whereas in the mountain forest ground level vegetation is much more rich and dense, a ‘giant salad bowl’ for the gorillas. This structure and botanical composition of the central African lowland forest affects the range and dietary regime of the western lowland gorilla. It necessitates long travel in search of food, particularly preferred fruits and thus the western lowland gorilla’s extended territory in comparison to the mountain gorilla.

Tracking lowland gorillas is thus not easy and does not have the same success rate as with the mountain gorillas. Indeed I had tracked lowland gorillas several times in nearby Gabon without success. But here in Dzanga the WWF researchers were working with the Ba’Aka to aid the process of habituating the gorillas to humans. If it were not for the Ba’Aka, their incredible knowledge of the forest and their unerring ability to track the wildlife it would not be possible to track and hence habituate the gorillas.

W arrived at Bai Hokou research camp, collection of huts with few amenities and little entertainment except for a basketball hoop. This struck me as a little challenging for the pygmy trackers. We headed off into the forest with Mobambu, our Ba’Aka guide.

As the gorillas were not yet fully habituated they were wary of our presence, even aggressive. On three different occasions the silverback charged us. He began with a low coughing, which worked up in pitch and frequency to a loud screech bark. And then he would charge. His charge was noisy and sudden. A rapid blur. Our reaction was instant and instinctive: we cowered down in fear. Submission was immediate and unconditional. Appreciation of his strength was total.

It ended as quickly as it started and he crashed back into the undergrowth. I breathed again and reckoned that he must have stopped some six to eight metres away – to my mind it felt like a lot less. It was an experience that produced adrenalin like no other experience I've ever had before.

We would then wait. Ears and eyes straining, I would try and work out where the gorillas were. It was unnerving how silently they moved through the forest. After several minutes Mobambu said that they had moved ahead of us, unseen and unheard. Mobambu then led us in an arc in case we had disturbed the gorillas and they wanted to return to a spot. I was totally disorientated but we moved confidently forward under the absolute guidance of Mobambu who would uncannily bring us into contact with the gorillas having walked in an arc of some several hundred metres some ten minutes later.

Although it was hard to see through the vegetation, I managed to catch some remarkable views of the group. Unlike the mountain gorillas where you invariably spend the majority of your time looking through a camera lens to get the picture perfect postcard shot, here with the lowland gorillas it was about moments and the experience as a whole. A mother with a young baby stood up and clapped her hands together. I was unsure if this was to warn us against coming any closer or to attract the attention of the silverback, her defender, to prevent us from doing so. Whichever we erred on the side of caution and kept our distance. Inevitably this provoked the curiosity of an infant who edged closer to get a better look. He was further intrigued when I started hiding behind a tree, playing a game of peek-a-boo with him. Meanwhile another juvenile totally ignored us, breaking a termite mound into fist-size pieces and then shaking the termites into his hand. Handful at a time he would stuff the termites into his mouth.

It was in one sense a very special and gentle experience. Deeply emotional and one that I feel not fully able to articulate. On the other it was a thrilling adrenaline rush, not least to be charged so often by the silverback. He was extraordinary and there is simply no way to anticipate or prepare yourself for his full size and strength. His power is awesome.

On our last day we went hunting with the pygmies. I was a little cynical, wary of the fact that many ‘experiences’ with indigenous peoples are often mediated for public consumption, mediated for the west. I was worried that this was going to be a commercialised, touristy experience. It wasn’t. It was remarkably genuine, quite disturbing, but very, very memorable.

The main forest pursuit of the Ba’Aka is hunting. It is also the most eagerly awaited and anticipated activity within each community and hence, as we set off on the hunt, there was a real singsong atmosphere. With Bokia nets draped over their shoulders, everyone was upbeat and full of optimism, full of banter and laughter. I waited with bated breath for one of them to break into song, “Hi ho Hi ho and off to work we go”, but refreshingly Disney has not yet infiltrated the jungles of equatorial Africa.

Suddenly the Ba'Aka left the path and entered the forest, a tangle of roots, branches and lianas. But this did not deter the Ba’Aka who moved quickly and nimbly though the forest, their diminutive stature no evolutionary quirk. One woman, Essandja, turned around and uttered an onomatopoeic “Twock, twock, twock” in imitation of my clumsy progress. She smiled and laughed. Her laughter was natural and infectious. I laughed at her joke, enjoying the camaraderie of the hunt. That was until my rucksack and I become ensnared by another vine. I cursed as Essandja slipped ahead of me into the jungle, never once getting her net caught in the vines and never looking down at her feet.

Collectively – the whole hunt is one of cooperation and togetherness involving men, women, children and on this occasion a young baby of six months – an area of forest was chosen in which to string up their nets. Using wooden hooks to attach them to trees, the nets were rapidly deployed in a large semi circle. There were some ten hunters in our party each carrying a net of some fifteen metres in length and a metre in width. Thus in total the semi-circle was approximately one hundred and fifty metres long and a metre high. Each hunter then checked that his or her net was strung out properly, cutting notches into trees in which to hang the net from, using vines and twigs to ensure that the net is firmly attached to the ground. The work was quick and thorough, their fingers wonderfully skilful. Little was left to chance; no gaps were left, no opportunity given to their quarry to escape. The trap was set.

Then the commotion began. The Ba’Aka began shouting and screaming. They pounded the undergrowth with branches, machetes and leaves to scare the animals out of hiding and drive them into the waiting nets. My heart raced in anticipation and expectation as they moved towards us, the noise building in a crescendo. And then there was silence. I looked around, bemused, trying to ascertain what and happened, what was going on. Had they caught something? But no, they had caught nothing. No success. The nets were dismantled, bundled onto shoulders and the hunters move on.

The process was repeated several times until we heard a bleat of distress. Ecstatic shrieking and childlike euphoria ensued as everyone rushed to the spot. “Mboloko. Mboloko” they shouted: a young blue duiker had been caught. Struggling vainly in the net, the duiker’s eyes were full of terror. Part of me wanted to turn away but it is a natural process and the Ba’Aka were not hunting for sport.

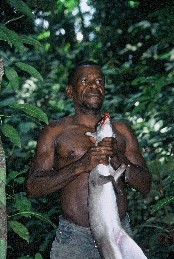

The duiker’s legs were broken in what to my sanitised western mind, conditioned by supermarkets and processed packages of meat, seemed like savage brutality. To the Ba’Aka it was a necessity – to lose the duiker at this stage would be a prodigal waste of time and energy. So as casually as one might snap a twig the hind legs of the small antelope were broken and it was dispatched with a heavy blow to the head. Again not a very comfortable sight for a westerner to watch, but this is the way they live; this was an authentic pygmy hunting experience.

A second duiker was caught. The hunt had been successful and it was time to divide the spoils according to the rules of the group. The hunter whose net the animal was caught in claimed the head and foreleg. The next person on the scene received the other foreleg and so on. The division of the spoils occurred without discussion. Marantacae leaves were spread out on the ground and the two animals were laid out on them. The butchery began without fuss. They worked swiftly and nothing was wasted, even the blood was shared out – it is used in cooking. The leaves are folded together and bound with twine; each hunter departs with a neat package for the pot. It had all taken place in a matter of minutes with little trace remaining of the bloody process. Literally nothing was wasted.

The whole experience in Dzanga

has been so completely and utterly absorbing, with so much to take

in, that I felt as though I had been here for months. Home felt weeks

distant, yet I had only been here for a few days.

West African had won again. But this time it had won me over. I was blown away

in a way that I have not been for a very long time.

|

|

|