Snow or rock - Finding a Snow Leopard in Ladakh

Emerging from the plane I gasped in shock. Not only from the freezing early morning temperature - believe me in contrast to the sweltering heat of Delhi from which I had just come the sub-zero temperature was breathtaking – but the staggering mountain scenery which hemmed in the runway. Like an icy series of savage waves, the surrounding mountains announced in no uncertain terms that we had entered the frozen realm of the snow leopard. The harsh and forbidding beauty of the landscape emphasised the futility of our task, namely trying to see a snow leopard in such a daunting wilderness.

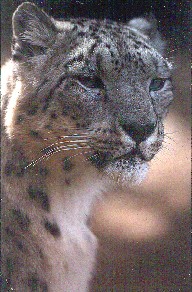

Listed on the World Conservation Union’s (IUCN) Red List of threatened species as endangered, the snow leopard is one of the least known and certainly most elusive animals in the world. Not only is it uncommon but the snow leopard is wary and mysterious to a magical degree preferring harsh, remote, mountainous terrain - the few thousand that remain live in the mountains of Central Asia, Bhutan, China, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Russia and India. Furthermore it is so well camouflaged that in the places that it chooses to lie one can stare straight at it and yet fail to see it. It melts into the background so effectively that there is little wonder that this majestic animal has achieved near myth status. Our task was certainly not going to be an easy one.

Undeterred by such information and the poor statistical odds of seeing a snow leopard – under 5% - we had come to Ladakh, the land of many passes and snow clad mountains. Covering an area of some 90,000 square kilometres (roughly the size of Scotland) in the far north of India, Ladakh is sandwiched between two vast mountain systems, the Himalaya to the south and the Karakoram to the north. It is thus high and remote, perfect snow leopard habitat.

To further try and improve the odds, we enlisted the help of Rinchen Wangchuk, Field Director of the Snow Leopard Conservancy in Ladakh. The Snow Leopard Conservancy is dedicated to demonstrating innovative grassroots measures that lead local people to become better stewards of the endangered snow leopard, its prey and its habitat. Under Rinchen’s guidance we hoped to beat the odds.

On arrival in Leh, the capital of Ladakh, we were eager to head straight into the mountains and maximise the time we could spend looking for a snow leopard. Rinchen however advised against this, warning that the effects of Leh’s 3,500 metres could be unsettling. There was nothing for us to do but to slow down, relax and acclimatise – part of Leh’s charm is that there is little to do but slow down, relax and acclimatise.

The town itself is dominated by the Old Palace, which sits precariously on a hill to the north. Below it nestles the Old Village, a fascinating labyrinth of tiny streets in which Indian soldiers and Kashmiri souvenir sellers have replaced the exotic traders from Turkistan, Afghanistan and Tibet. The inhabitants of Leh are courteous, happy people and wherever I went, wizened faces and rosy cheeks broke into a cry of the all-encompassing jule (pronounced ‘joolay’), which could mean hello, bye, thank you and please! So if there is a word of Ladhaki that you must learn, it is jule.

After several days of acclimatising and discovering the exquisite charms of Ladakhi culture, we loaded up our rucksacks and headed out into the Hemis National Park. A high altitude area of some 600 square kilometres, the park was created in 1981 in the eastern part of the cold desert of Ladakh for the conservation of its unique flora and fauna. Trekking through narrow dramatic valleys and steep hillsides of barren rock, it was easy to see how Ladakh had earned the epithet ‘Moonscape’. We crossed wobbly log bridges spanning gurgling glacial streams, heading deeper into this high, arid environment, the lair of the leopard. It was rugged and stark and seemingly lifeless.

But not to an expert eye such as Rinchen’s. Every so often Rinchen would kneel down by a rocky overhang and indicate a scrape – a scuffed area where a leopard has stopped and scraped the ground with its back feet. Rinchen explained that scrapes were an important form of communication for this solitary animal and that there can be as many as two hundred scrapes in one kilometre of pathway. He would point out tracks on the ground that revealed the immense size of the leopard’s paw or would say, “That’s a stool. Possibly two, maybe three days old.” But perhaps most disconcertingly he would kneel under a rocky overhang and sniff the powerful pungent odour of snow leopard spray.

Such tantalising signs were clear evidence that there were snow leopards in the area and filled me with the hope, however vague, that we might actually see one. But before I got too carried away and overexcited at the prospect, I brought myself back down to reality with the thought that many researchers had spent months in the field without so much as a glimpse of this elusive animal. Indeed the author Peter Matthiessen had spent months in Nepal and written a whole book entitled, ‘Snow Leopard’, yet had not seen one.

In Husing valley we passed several video and stills cameras that were triggered by sensors powered by solar panels. (99% of all photographs of snow leopards are of leopards in captivity or via such sensors). The cameras were sighted on well-used leopard trails or under rocky overhangs that were used a spray sights. At each one Rinchen would stop and take down details of the recordings. One camera had had just six sightings in the past thirty-five days and three of these had been at night – further proof of the elusiveness of the snow leopard and the difficulty of the task ahead of us.

If I was to be denied the thrill of seeing a leopard, at least I wanted to enjoy the austere beauty of its domain. At every opportunity I would scramble up to a ridge or pass and survey the world below from my vantage point. The mountains all around me were still and vast, an impenetrable inner sanctum of stone and snow stretching in every direction as far as the eye can see. The stillness was oppressive, the silence thunderous as the sun beat down on the arid landscape. Occasionally the stillness would be broken by the shadow of a golden eagle passing over the valley floor or the silence broken by the strained call of a snow cock echoing across the valley. Looking out each day over such majestic valleys and surrounded by the towering peaks was uplifting and awe-inspiring.

One night I heard a swishing sound against my tent. Half asleep my febrile imagination thought it might be a snow leopard rubbing its tail against my tent. The truth was somewhat more mundane – it was snowing heavily and every ten minutes or so the accumulated snow would slide down the side of my tent. Although the snowfall was perhaps unexpected I should not have been so surprised seeing as we were over 4,000 metres and in the Himalaya, which translates literally as the alaya (abode or home) of hima (snow).

Emerging out of my tent the next morning the landscape had changed spectacularly with the overnight snowfall. Covered in a foot of snow, the dull browns and ochres of the rocky cliff faces had been replaced a dazzling whiteness. Moreover rather than simply transforming the scenery, I presumed that the snow would make it easier to spot and track a leopard. However Rinchen corrected me, saying that, “Snow Leopards do not like to get their feet wet. They will stay low until the snow stops and only then will they think about coming out.”

I thought to myself that perhaps this most mysterious of cats has been misnamed – rather than being a snow leopard it should be called a rock leopard. With its large paws, short limbs, powerful muscles and long tail the snow leopard is well adapted to moving around precipitous cliffs and rocky ledges. Added to this its camouflage is so effective, blending in with the rocky cliffs that on more than one occasion I was convinced that I had seen a snow leopard through the spotting scope, only to discover that after several minutes it had not moved and was in fact a rock. The name, ‘rock leopard’, if less romantic is certainly a more descriptive name for the species.

With the snow still falling we headed out of camp and up the Tsogsti valley. Visibility was poor, all the peaks were hidden in cloud, and I thought we had little chance of seeing anything. But that was not taking into account Rinchen, his expertise and phenomenal eyesight. “There are some blue sheep, high up to the right of that gully,” he said quietly.

Binoculars fixed, we all scanned the snow-covered slopes above but to no avail. Rinchen patiently gave us a little more instruction and direction until one of us cried, “Uh yeah, I’ve got them now.”

The main prey of the snow leopard, the blue sheep is a short-legged, strong, broad-backed animal with large curved horns that is not dissimilar to an ibex. Never more than eighty metres from steep rocky faces where it feels most safe and less vulnerable to attack from wolves, the blue sheep is quick and sure-footed. But even on the vertiginous slopes the blue sheep is not free from danger for this is the favoured hunting ground of the snow leopard. A case of out of the pan and into the fire?

The movements of the snow leopard are inextricably linked with those of the blue sheep on whom she depends for food. We trudged on through the snow in the hope that the prey might lead us to the predator only to come across more blue sheep further up the valley, this time a young male group of about six. But even Rinchen was beginning to struggle with the poor light and we decided to return to camp and lie low for the rest of the afternoon like our mysterious quarry. Instead I immersed myself in Peter Matthiessen’s ‘Snow Leopard’ – if I could not have the real thing I sought solace in his equally unsuccessful attempt to do so.

The next morning we awoke early putting faith in the adage that ‘the early bird catches the worm’. We were duly rewarded with a spectacular dawn of bright blue, cloudless skies. We headed up the Lungmoche Tokpi valley, the white pristine peaks of Stok Kangri and the surrounding ridges beckoning us forward. The brilliance of the light, the crisp air, the contrast of the white serrated edges against the blue background made for a truly stunning setting. It was fantastic to be in this remote wilderness.

Stopping on a ridge to catch the sun and try and warm up our feet – it was minus eight degrees centigrade in the shade according to Rinchen’s thermometer but a good deal colder according to our toes - we began scouring the surrounding valleys for signs of life. High up to the north were some blue sheep. Further down I thought that I could see prints leading up to a rocky ledge that would have been perfect place for a snow leopard to sit and watch the world go by.

“Rinchen, Rinchen” I cried excitedly pointing him in the direction of the tracks, “Snow Leopard tracks!”

Rinchen examined the area where I was pointing for several seconds. It seemed like ages before he replied. The delay seemed to imply that there was something there, that I had spotted snow leopard tracks.

“No. It’s nothing. Just snow falling from the ledge and rolling down the hill.”

I could not believe him. I did not believe that I was wrong and so disastrously so. But Rinchen was the expert and my eyes had been fooled on many previous occasions. I had to concede once again to his vast experience. Just one quick last look - they did look remarkably like tracks to me. My spotting pride still smarting, we returned to camp for breakfast.

After breakfast Sonam, our cook, began searching the surrounding cliff faces for any signs of snow leopard or more likely their prey. I was grateful for his commitment but would have appreciated him giving us a little more time for our daily ablutions - the loo tent was positioned not far from the spotting scopes and certainly in their line of view. My need was greater than my fear of stage fright so I entered the loo tent.

Sonam began shouting excitedly. I thought to myself

why can’t

he leave me in peace. But then I heard Ricnhen’s voice full of

genuine excitement and the tantalising words ‘snow leopard’.

I made it to the spotting scopes as quickly as I could only for Rinchen

to tell me that the leopard had disappeared behind a rock. I could not

believe the irony of the fact that for our one and only sighting of this

most secretive of creatures I had been caught with my pants down, both

metaphorically and literally speaking.

My disappointment was only too transparent. I knew all too well that

a glimpse of a snow leopard was all that I could have hoped for and

I had missed that opportunity. Rinchen told me to be patient. He tried

to shake me out of my disappointment by saying that the leopard would

move into the sun shortly and we would get another chance to see it.

Thankfully Rinchen knows his subject. The leopard moved back into view.

“There. See the patch of snow. The ledge above, just to the right.”

“Where?” I replied, the camouflage of the leopard defeating me. Despite the magnification of the spotting scope I could see nothing and was in awe at how Rinchen and Sonam had seen anything. But then a rock seemed to come alive. It was the leopard moving.

Few superlatives can describe the elation that I felt. It was a pure magical high. You will have heard it said before that these creatures are awesome beasts and I would like to add my own particular perception: the snow leopard is a magnificent beast.

Although it was high up on the cliff face on the opposite side of the valley, several hundred metres away, I could clearly see its wonderful coat of pale misty grey, with black rosettes that were clouded by the depth of the fur. I marvelled at its superb camouflage, the smoky grey spotted coat blending perfectly with the surrounding rocks. I was mesmerised by the extraordinary length of its luxuriant tail. Some three foot in length, the tail helps balance the snow leopard on steep inclines and can be wrapped all the way around its body for warmth.

It was climbing, looking for a better vantage point, moving effortlessly, its short limbs adept on the vertiginous slope. Its movements were assured and powerful – I could well believe the stories that it could leap up to a distance of thirty feet. It was a paragon of that rare combination of raw power and masterful control that few animals can aspire to. It settled itself, seemed to look right at us – Rinchen confirmed that they have excellent eyesight as well as hearing – and then began to groom itself.

In contrast to the slow, languid movements of

the snow leopard down in the valley we were frantic with excitement.

The atmosphere was electric.

The excitement was tangible. Broad grins, elated eyes, mutterings of “Incredible”, “Beautiful”, “ So

lucky”. And I think also disbelief – although we had been

hugely hopeful of seeing a snow leopard none of us actually believed

that we might. But against all expectations we had!

|

|

|