Chapter 10 - Tibet

Today was Tibet. We were both thrilled to be on the threshold of this ancient and mysterious kingdom, remote and untouched for so many centuries due to its formidable geography. Tibet is one of the most isolated areas in the world, guarded by the Himalayas to the south, the Karakorum to the west and the Kunlun Mountains to the north. An area the size of Western Europe, much of Tibet is above 4,000 metres hence its epithet ‘Roof of the World’.

Unassailable, Tibet is a land not only geographically alien from the dry savannah of Africa that I was brought up in, but also a world so culturally different from any that I had visited beforehand. These cultural differences are due to Tibet’s reclusive nature and the fact that the kingdom cut off its ties with the rest of the world in the late nineteenth century. Tibet is an exotic land of nomads, yaks, sky burials, monasteries, red-robed monks and rarefied religious perceptions, or so ‘Tintin in Tibet’ and other stereotypical images would have me believe.

The Tibetan people themselves

are a friendly, no-nonsense sort of people who love the exchange of

gossip, for whom, due to the land being remote

and sparsely populated, every encounter is all important, not unlike

the Bedouin. “Western visitors so diverse in personality...all

agree in describing the Tibetans as kind, gentle, honest, open and cheerful,” says

Hugh Richardson in his ‘Short History of Tibet’.

Such cultural difference and inaccessibility lends itself to a childlike

curiosity and desire to see the forbidden, that which is out of bounds.

For generations this led to attempts on the fabled forbidden city of

Lhasa, from that of Father Desideri who stayed in Lhasa for thirteen

years in the early eighteenth century to the four-month stay of Englishman

Thomas Manning in 1811. But despite these visits Lhasa revealed little

of itself to the outside world until the machinations of the Great

Game between Russia and Britain precipitated Younghusband to force

his way into the city in 1904. Very few others visited Lhasa during

this first half of the century with the daring exception of Heinrich

Harrer. But even Harrer’s enchanted stay in Lhasa came to an

end with the arrival of the Chinese who shut the door on Tibet.

The Chinese ‘liberation’ of Tibet in 1950 led to the death of over one million Tibetans, an assault on the Tibetan traditional way of life and the wholesale destruction of their monasteries and religion - not unlike Henry VIII and his dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s. The Chinese created the Tibetan Autonomous Region, a misnomer, a truncated version of the former Tibetan kingdom, much of its land swallowed up by the provinces of Yunnan, Sichuan, Gansu and Qinghai. The Tibetan Autonomous region is not only smaller in area but contains a third of its former population, two million Tibetans not six million. Whilst this was going on the British government and the rest of the world were appalling in their silence - during the conquest of Tibet, only El Salvador condemned the Chinese aggression. Britain like many other countries did not want to incur Chinese disapproval, and some may argue that their position towards China has changed little today.

From 1950 onwards tensions between the Tibetans and Chinese came to a head during the Tibetan New Year of 1959, with huge crowds descending upon Lhasa. Fears that the Dalai Lama was about to be kidnapped at the celebrations, where he had been asked to attend without his usual retinue and bodyguards, led to anger and discontent spilling out on to the streets. Thousands gathered around the Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama's summer palace, to protect the Dalai Lama with their lives. On 17 March as the Chinese began shelling Lhasa the Dalai Lama fled across the border to Dharamsala, India, where he still resides today. In the three days of violence in Lhasa that followed it is estimated that the Chinese killed some 10,000 to 15,000 Tibetans. General Pinochet is estimated to have killed some 3,500 Chileans during the 1970s and look at the furore that is occurring over his extradition from Britain at the moment. Has there been any such outcry about Tibet?

From Dharamsala the Dalai Lama has been calling for the autonomy of his people, for a return to basic human rights and freedoms. His desire for dialogue has even led to his concession of demands for full independence and offering the Chinese the right to govern Tibetan foreign affairs. The Chinese have been typically recalcitrant and stubborn, refusing any dialogue. Their refusal to give an inch could eventually lead to bigger losses with the possible, though unlikely, independence of Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and perhaps even the Special Economic Zones set up in 1979 by Deng Xiao Ping to encourage development and the open door policy. Yet given the continued flexing of its military muscle over Taiwan, notably the missile crisis of 1996, China will not give up without a fight and perhaps atrocities and oppression far worse than Tiananmen in 1989.

The Chinese prised open the door to Tibet in the 1980s, officially allowing foreigners into the ‘Roof of the World’ in late 1984. But it has not been an all inclusive open door policy. After a series of demonstrations led to an uprising in 1987, the Chinese acted swiftly by ejecting all foreign journalists (still to this day journalists are very unwelcome in Tibet) and individual travellers. Since then access to Tibet has fluctuated according to Chinese sensitivity and whim. This year, 1999, is the fortieth anniversary of the Tibetan uprising and the Dalai Lama’s flight from his homeland and thus the authorities are especially prickly. Foreigners are only allowed to travel recognised routes in Tibet or with guides and official permission, and two cyclists following the Mekong did not qualify on either count. Ian and I would have to tread carefully.

*

Ian was fast asleep, to awaken him would have been unfair, so I quietly rose and went out to wander around the village and to ‘recce’ the road ahead. As I walked out of Yanjing I passed groups of school children, heads burrowed in books, doing a bit of last minute revision for some dreaded test. But unfortunately for their marks in the test and their teacher’s sake, I was much more interesting and entertaining than their books. The fact that I was wearing shorts, revealing my hairy, skinny legs in all their glory, caused much hilarity and amusement. I know that kids will laugh at anything, to them it is harmless fun, but it was early in the morning and I was not quite ready for their giggles at my own freak-show expense.

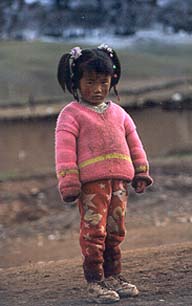

Pitter-patter, pitter-patter, the sound of hurried tiny feet. They stopped behind me. A shy, gasped greeting of “Ni hao” (hello). I turned around to see a shock of pigtails, wide eyes, weather-tainted cheeks and a hand thrust forward. The little girl was delightfully cute and her gesture wonderfully warming, so much so, that I shook her hand gently, a big smile spreading across my face. That one little gesture heartened me for the rest of the day.

To you it may seem an insignificant moment and that I am just indulging in sentimentality, but when you are always the centre of attention, an object of ridicule such an act is touching. Justin Hill in his wonderful book ‘A Bend in the Yellow River’ about teaching in China for two years describes what it is like to be subjected to such relentless scrutiny:

“Walking in the streets we were always the centre of attention. Girls standing in the doorways of shops would call to their friends, “Hey, come quick, a foreigner!” and their friends would dash headlong through the doorway and fall over themselves as they pointed and waved and shouted. Mothers would pick up their children, point and say, ‘Look a foreigner!’ Then the child would burst out crying. ‘Don't be frightened,’ the mother would coo, while I went off feeling like the Elephant Man. The peasants in the town would line up on the street laughing or quietly curious as they watched my show: Foreigner Walks Down Street; Foreigner Stops; Foreigner Speaks Chinese; Foreigner Buys Potatoes and Cabbages; Foreigner Walks Up Street - hilarious stuff!” That was after Justin's first few days in Yuncheng and perhaps a little extreme, but I can empathise with what he felt.

Having breakfasted on noodles and fried egg yet again, it was time to run the gauntlet and enter the Autonomous Region of Tibet. We headed out of Yanjing trying to be as inconspicuous as we possibly could, avoiding the road and officialdom by a path that wound its way through the houses. Once out of Yanjing we rejoined the road and cautiously went on our way, half expecting to run into a checkpoint and to be turned back. I feared the worst, and was so apprehensive that I was wary of every jeep that passed us, believing that it might bring the law down upon us - occasionally in real fits of angst I would take cover.

“We’re in. We’re in. I can’t believe that we are in Tibet! And it’s been so easy...” In spite of our paranoid we were both hugely relieved to be in Tibet and believed that we now could possibly make it to the source. Perhaps premature and tempting fate too much but for most of the day nine words were going through my mind. Those words would either be on a telegram or left on an answer-phone: ‘We made it. We’re coming home. I love you.’

But those words were still a thousand kilometres away, a distance that probably involved many more climbs such as today’s. We must have struggled uphill, solidly uphill with no respite, in low gear for some forty kilometres. Worse still this climb was done on a breakfast of noodles and a packet of biscuits, there being no food stalls, nothing to supplement our diet en route. I tell a lie, there was one shabby hut where, with the greatest reluctance, the proprietor, weather darkened face, slowly struggled to his feet and served us a can of sprite and a packet of crisps, all without so much as a word. The crisps were stale but welcome nourishment, giving us strength to battle against the terrain and just as important the elements. The sun was strong, the altitude giving it extra penetration, the wind gusting and buffeting, welcome to Tibet.

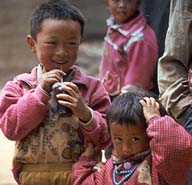

As the shadows lengthened, we made it to the top of the pass and speeding down hill, had to keep our eyes open for a suitable camping spot. We found a secluded area slightly back from the road by a small stream. Well, we had thought that it was secluded until an excited group of Tibetan kids descended upon us. Smiling faces, dirty clothes and snotty noses, they crowded around us. Some were bold, others more shy and retiring but all were interested. They were curious of our equipment, eager to give a hand with the putting up of our tent - at which they were surprisingly proficient for the first time erection of a tent, unless of course other crazy foreign cyclists had preceded us, doubtful.

Ian gave them a ‘polo’ each as thanks for their help. A well-meaning but fatal mistake, as after this every time we opened up a pannier they expected a gift or a sweet of some sort. I am a great believer that when travelling it is much better to give of your time rather than presents. If you are to give gifts, it is often much better to give them to parents or teachers to give to the children - this does not undermine parents to the same extent and does not create the ‘begging for hand-outs’ mentality in children. There can be few more disturbing acts of travel than to find in some remote area a little girl demanding sweets or ‘bonbon’, or a young boy asking for money.

Their curiosity turned into fascination as Ian got out our dragonfly stove and began preparing dinner. Crowding round, jostling for position, with wide attentive eyes they followed and scrutinised his every move. What did they make of our bizarre gadgets and us? This diversion allowed me to slip away to the stream and to do some washing. However, my departure did not go unnoticed and I was quickly followed by a couple of the more inquisitive boys. When they realised that I was merely washing clothes, obviously women's work, they lost interest and returned to the far more exciting and novel stove. This allowed me the time and freedom to complete my own ablutions, which involved tricky stages of undress. At one particularly vulnerable moment I was spotted and squealing with delight at my predicament, the kids could not resist the temptation to come closer and laugh at my exposed, very white backside. Evidently this caused much amusement, not least amongst Ian who was rolling on the ground in stitches of laughter.

“You, you put them up to this,” I accused, whilst trying to regain some sense of propriety. My dignity restored, the kids had to hurry home, wherever it was, and Ian and I, after some freeze dried food, settled down to scrabble and sleep.

*

Heavy dew had dampened much of the firewood that we had collected thus Ian decided to use some fuel from the stove to act as a catalyst. It worked and he managed to get the fire going, as well as the contents of the canister and the surrounding area. An interesting, if environmentally unfriendly, display in pyrotechnics that was only controlled after a few minutes and much stamping and stomping on smouldering patches of grass.

Shortly afterwards we were surrounded by an adult audience who did not interfere but sat quietly, passing the occasional comment amongst themselves about our antics. They were not threatening or intrusive, merely fascinated by our equipment as the children were last night, and became engrossed in discussion trying to work out what each item was and what it was used for. Our bicycle pump was the subject of heated debate, even to the extent that it was passed around so that everyone could feel its weight and examine it from a variety of angles. The argument was only resolved when Ian picked up the pump and moved to his bike and motioned pumping up a tyre, resulting in a nodding of heads and looks of ‘I told you so.’ It was fortunate that they had not arrived ten minutes earlier as I am not sure what they would have made of the blazing fuel canister.

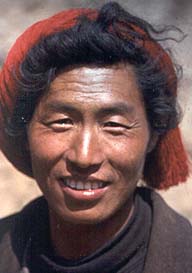

Once on the road we passed whole groups of Khampas, the notorious nomadic warrior tribes of Kham, as eastern Tibet is called. The Khampas have a long history of conflict and have constantly harassed the Chinese, fighting the PLA virtually alone between 1950 and 1959, while the Dalai Lama and his supporters, according to Michel Peissel, “collaborated with the Chinese in order to hold on to their privileges.” The ban on travel in many parts of Tibet is said to be partly due to the remoteness of the area, but also due to the Chinese fear of the Khmapas.

I remember Peter Goullart talking of the Goloks and Khampas with wariness in his emotive account of Naxi life in his book ‘Forgotten Kingdom’. “Personally, I would rather deal with a Chinese or Nakhi (Naxi) robber than a Tibetan one. A Chinese or Nakhi robber seldom kills his victim. He robs you, but he does it with a degree of finesse and delicacy, and at least leaves you your underwear to enable you to reach the nearest village with a modicum of decency.”

And yet in spite of their sheathed knives at their belts, these Khampas were far from intimidating, rather the opposite. Smiling and friendly, each group that we passed wanted us to stop and spend some time with them. Tall and erect they walked with a bearing, clearly defiant and proud of their heritage. They had a presence that many of the other people we had come across, namely the Han Chinese, lacked. And that is not just me cowering to their fearsome reputation, they do have real character and spirit. Their faces were wide and beautiful, striking, with intense eyes. Their hair, long black and tussled, was worn in plaits and bunched on the top of their heads, tied with red cord. They were happy to see us and wished us well, waving us goodbye and signalling good luck.

Such warmth of welcome is tremendously uplifting to a weary cyclist who often questions the sanity of his undertaking. Moments like those with the Khampas stick in the mind. In one small village we were surrounded by thirty children, beaming faces, wide smiles overjoyed at seeing two foreigners on bikes. Their excitement was so great, almost rewarding, and yet their disappointment at our departure palpable.

Another time we met the only other foreigner that we were to come across in Tibet, Chris, a doctor form Sydney who had been working in China on and off since 1982. “I’m here trying to do something about iodine deficiency and goitres that are caused as a result,” said Chris whose work has recently received the recognition of the Chinese government, who are now keen to help. He thought that we were crazy and said that he would never forget Ian’s “pained expression” as we were struggling uphill, “It will remind me of what true pain and effort is. I admire you for your typically British resolve.”

The road that day deteriorated into a rough rutted surface that made cycling difficult. Stones and holes would cause wheels to bounce uncontrollably meaning a loss of purchase, a jarring time for wrists and forearms. It was wearing and frustrating rather than physically tiring, more the mental strain, a war of attrition. The first to break was not Ian or me, but my front rack, again. A botched patch up job with gaffer tape would hopefully see me through to Markam some twenty kilometres away.

Markam was no use to us in terms of bicycle repair and I was forced to soldier on as best I could. What Markam did provide however, was a welcome meal in which we stuffed ourselves, having little difficulty in polishing off the four dishes that we ordered. After Markam we left the wide plains that we had been cycling through for most of the day and began to climb and climb. By the time that we decided to pull up pedals and pitch camp for the night, we must have been at a height approaching 4,500 metres. Regrettably, perhaps foolishly we did not have an altimeter, but whatever the statistics, we certainly had a brilliant view of rolling hills and mountains for as far as the eye could see.

*

I awoke to find the tent and bikes covered in an icy frost, the surrounding area sparkling in the early morning sunshine. Cold but crisp and clear, the sun quickly warming, it was a magical moment to sit outside the tent, enjoy the silence and rule like royalty over the imperious view.

I was roused form my morning reverie of scenery and silence by two things. Firstly, the sun going behind a cloud that made me shiver with cold and realise that it was still freezing - overnight it must have dropped down to -5 degrees centigrade, whereas during the day the temperature had been in the high thirties, felt like forties. The other was the distant rumbling, the grinding of an engine trying to cope with the gradient, which signalled the arrival of a truck, rather a convoy of trucks.

At first we suspected that this army convoy had been sent to apprehend us, although we did think the amount of trucks a little extreme for two rogue cyclists. Later, we discovered that these trucks were transporting logs. Where from I do not know, possibly Myanmar or the forests of south-eastern Tibet, but each log was at least one metre to a metre and a half in diameter and that throughout the day over two hundred trucks passed us. I do however know that whilst we became filthy with the dust thrown up by the convoy, somebody, somewhere, was becoming very rich.

The road in the morning rattled and bounced us downhill. “It’s like a BMX track,” said Ian. I agreed with him that it certainly was bumpy, but did not question him on how he happened to know so much about BMX’s and their tracks. Concentration and mountain bikes were both essential for such roads, and we would certainly have been struggling without our Kona bikes that handled the terrain superbly throughout. I would have loved to have pushed the bikes to their limit, but we still had many hundred kilometres to go, so caution, though painful on the hands and fingers due to continual braking, was still necessary.

The scenery, mountains, pine trees, chalets, shepherds and sheep, was vaguely reminiscent of Switzerland. But there was no blonde hair, no pale faces, only black hair and faces incredibly darkened and wizened by the sun and wind. I had not expected to see such dark faces in Tibet. Yes, cheeks reddened and raw from the climate, but not the scorched blackness that surrounded so many white smiles.

After several hours of jarring and juddering downhill, we reached the Mekong and the small settlement of Zu Cha where we had lunch in a friendly Tibetan hut. The heat here at the bottom of the valley was searing, energy sapping. The scorching sun was more akin to the Costaguana of Conrad’s ‘Nostromo’, which I was reading in the shade as we waited for the heat to go out of the day. We preferred the shade and the delay to being ‘Englishmen out in the midday sun’, though when we eventually left the hut at 3.30 the Tibetans still thought us crazy, that it was still too hot to continue.

We began a slow, steady ascent out of the valley through a series of spectacular hairpin bends that was to take us to seven o’clock, some twenty-one kilometres later. Even the non-mathematicians amongst you will realise that that is slow going, a reflection not of our levels of fitness but the gruelling combination of heat, terrain and gradient. During the climb I had been wracked by cravings of food. Not Chinese food or the less appealing Tibetan food, not the meagre portions of nouvelle cuisine, but a good hearty, stodgy English meal. Images of Shepherd’s Pie, Steak and Kidney Pie, chips and gravy flashed temptingly before my mind. Instead, when we stopped for the night half an hour short of the summit of the pass, I had to content myself with another flatulent-inducing freeze packed meal and console my stomach that it was just a matter of weeks until it could gorge itself. Still hungry, I had to take my mind away from my stomach by losing myself in the eerie silence that pervaded, the wind having dropped, not a stir nor breath breaking the quiet.

*

We awoke hot and stuffy in the tent, in marked contrast to the previous morning, but still with empty stomachs. An army ration breakfast of sausage and beans did little to appease the pangs of hunger and thus we set off with the intention of trying to make it to Zogang and a meal by nightfall. Four kilometres later we made it to the top of the pass that proclaimed itself to be at 3908 metres, the cluster of prayer flags10 testament to such heights. From here we dropped down some thirteen kilometres, the road thankfully being much better than the previous day, and then inevitably began to climb again through a narrow gully following a lively, fast-flowing stream.

Cycling was laboured, not physically exhausting or hard, just slow and ponderous due to the altitude. Our breathing was not sharp or difficult, our heads were not pounding or tormented by aches, our muscles simply sought a slower work ratio. Added to this the fact that we were both ravenous, we broke no records in our march uphill. Having climbed for some sixteen kilometres we came across an unexpected but extremely welcome lunch shack where we were warmly greeted by some soldiers, part of the never-ending convoy, and the mistress of the establishment.

The mistress of the establishment’s face was covered in white powder to protect her skin form the sun and give her a pale, presumably attractive, complexion. She was wearing white high heel shoes and a purple velvet dress with high slit up the side. No doubt the slit was to attract the attention of the soldiers if the rest of her appearance had not already done so. Her attire was bizarre to say the least, incongruous with the humble surrounds, and I could not help feeling that she was a little over-dressed for the occasion.

While we waited for various dishes to be prepared, salivating at the prospect, Ian decides to take his mind off food and try to entertain the children with his yo-yo. They found it an interesting concept, if a little difficult to come to terms with (hardly surprising given that until this century there were no wheels in Tibet except for prayer wheels), though one boy under Ian’s expert instruction quickly became a yo-yo convert. The eagerness in the eyes of the kids was great to watch but it was the amused twinkle in the eyes of one particularly gnarled old face that I found as riveting as Ian’s yo-yo performance.

The entertainment was interrupted by lunch, which we devoured ravenously, occasionally stopping to breathe, or to raise our heads to see the soldiers staring in awe at our appetites. The food was good, but at the time tasted great in spite of the local penchant to use chilli and lots of it. As we departed we filled up our water bottles much to the interest of the local Tibetan children whose outstretched hands wanted the used plastic bottles. We duly gave the empties to the kids, although their plaintive looks were so touching that I felt sad and inadequate, unable to be of real help to them.

After lunch the valley widened as we gained in altitude, revealing a wonderful high pasture with little sign of life, human or otherwise - although I did spot two timid marmots running off to the security of their holes. We had resolved upon an early stop, firstly to be able to get some washing done, both of ourselves and our clothes, and secondly to have a bit of a break, to give tired muscles a rest. We decided upon a grassy spot close to a stream, far enough away form the road so as not to arouse too much suspicion. Well we thought that we were a good distance from the road until a convoy of trucks started hooting their horns with amusement at the sight of Ian’s naked backside as he washed in the stream.

Despite the odd horn invading our privacy we relished the opportunity to cleanse body and clothes in the late afternoon sunlight. That was until a storm loomed large on the horizon, about to descend upon us at any minute, whereupon panic stations broke out as we tried to put up the tent in record time. Mercifully we were spared the full vengeance of the brooding clouds and simply made to appreciate the unpredictability of climate at this altitude and the need to be constantly aware and ready.

I awoke to find that our clothes, still damp from washing last night, had frozen stiff, as had the water in our bottles. Until the sun managed to peer over the surrounding mountains it was a bitterly cold morning, a morning that required porridge. Fortified by oats and warmed by the rising sun, we set off towards the summit at a steady seven kph. Each pedal drew us imperceptibly closer as the road seemed to wind on and on, a meandering climb that would not be out of place in Dante’s Inferno. To make matters worse we got a good dusting down from what had by now become the daily procession of army trucks carrying timber to Sichuan, denuding vast expanses of forest in an unknown area.

To compensate for the dust and the uphill toil there was the scenery. A wonderful glacial valley, though according to Ian the valley might have been caused by an ice sheet, surrounded by hanging valleys and snow capped peaks. The mountainsides were bare, barren and brown, the odd shrub eking out a lonely existence along the stream. It was quiet, peaceful and uplifting. I think that thus far in the last week alone, I have seen enough geography, stunning, beautiful and different, to last a lifetime - certainly, I have used up a lifetime of descriptive adjectives. And yet it goes on, continues to impress.

The summit of the pass, reached thirteen kilometres after setting out, was an exhilarating 5,008 metres. Neither of us had thought it that high, neither of us had been at this height before, both of us posed triumphantly by the stone marker announcing the height of the pass. Our excitement at being so high (16,500 feet, the source is only 300 feet higher at 16,800 feet) was almost matched by the adrenaline rush of speeding downhill for some twenty-six kilometres; it took us an hour to descend what would have taken us at least four hours to ascend. Scenery and the appreciation of took a back seat to the buzz and thrill of freewheeling.

Zogang, the first small town that we had come across since Markam was unappealing, and we simply fed ourselves and stocked up on provisions before getting back on the road. The road out of Zogang began following a large tributary of the Salween. It was a strikingly blue river that was flat and fast, not narrow and rushing, flanked either side by a valley of pine trees. It was picture postcard stuff, almost too good to be true, the kind of scene that I could imagine appearing in some US National Parks promotional video. It was made all the more appealing by the afternoon sun, and for the first time in a long time we felt relaxed and able to actually enjoy the cycling.

Along the river at various points we had our first experience of Tibetans asking for photographs of the Dalai Lama. To us, the rest of the world, the Dalai Lama is a prominent international figure who wears red robes, has a deep resonant laugh and who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989. To the Tibetans, deeply religious people, the Dalai Lama is the human manifestation of deity, more specifically, Avalokitshvara, The Bodhisattva of Compassion. Two years after the great thirteenth Dalai Lama died in 1933, a delegation of monks was sent to north-eastern Tibet to look for his successor. There they found, in the family of a poor horse dealer from Tagster, Tenzin Gyatso born in 1935, the reincarnation of the present Dalai Lama, the fourteenth Dalai Lama. Interestingly, the Dalai Lama’s elder brother Thubten Norbu was also an incarnate lama, Abbot of the monastery of Kum Bum. The Dalai Lama is also the very head of governmental structure in Tibet, or was until Chinese invasion and take-over in 1950s.

The fine line between the Dalai Lama's religious role and his role as a political figurehead is evidenced in China's paranoid toward him and pictures of him. In 1995 it became illegal to posses a picture of the Dalai Lama. In October 1996 monks were threatened with excommunication unless they signed denunciations of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. From the evidence of today’s demands for photos and the unswerving support of Tibetans for him in general, despite the fact that he is in exile in Dharamsala, such extreme measures have had little effect.

Hands outstretched in prayer, eyes and mouths pleading, the Tibetans were both insistent and persistent that we should give them a photo of the Dalai Lama. Such demands were to become a regular feature from now on, but unfortunately neither now nor later could we oblige.

*

Camping by the Salween tributary we awoke to a crowd of onlookers, this time curious rather than wanting. Ian tired with sleep was not the most receptive to this audience, but they were only trying to be friendly, offering us some food, merely inquisitive. They were intrigued by the smallness of Ian's short-wave radio, by our sleeping bags, by the stove for boiling ‘kai shui’, hot water - they left before they saw this drinkable hot water being adulterated by the adding of porridge oats. Used to privacy such early morning attention is a perhaps intrusive, but I could not begrudge their curiosity, especially as we and our paraphernalia were so alien to them. A crude parallel of what we must be like to them, is having a couple of Eskimos set up their igloo in your back garden, how receptive would you be?

As we set off that morning, a surprise lay in store for us, a treat: tarmac. After some seven hundred kilometres of duelling with the uneven, rutted surface of dirt roads this manna from heaven was most welcome. But what we were granted with one hand was cruelly taken away by the other for the tarmac petered out into the all too familiar dust and dirt after a few heavenly kilometres. We were being teased and toyed with, the Chinese road authorities having a laugh at our expense. We did not appreciate their wicked sense of humour and kept on believing that we were shortly to be reunited with our beloved tarmac, but it was not to be.

For lunch we stopped at a delightful Tibetan village, Tendo, where no Chinese and certainly no English was spoken, and we were thus left to fend with the few Tibetan words and numbers that I possessed, though invariably mime got the message through. Lunch consisted of packet noodles and yak butter tea, an interesting combination. I have noticed that almost all the places where we have stopped for food have been Han Chinese or at least their cuisine has been influenced by the Han Chinese, there being no other alternative. The Tibetans, or perhaps their cuisine, not up to serving food to hungry travellers. It has been said that the one good thing that the Chinese have brought to Tibetan culture is the introduction of their cuisine, the introduction of variety.

However, if Tendo lacks in the way of culinary delights, it more than makes up for this deficit with the charm and friendliness of its children. Faces are happy and smiling, attentive and alert, if a little reserved and wary of Ian and I. They have an unaffected charm, despite their runny noses (although I do empathise with the children on this point for my nose is continually streaming due to the climate and altitude. At first it was a major irritation, but soon became such a permanent feature of life on the plateau that I became used to it).

After Tendo I had expected the valleys to dwindle being replaced by the expanse of plateau. To be frank I had expected as much shortly after we had entered Tibet, which is after all the ‘Roof of the World’, the most extensive high altitude plateau in the world. Yet thus far, with the possible exception of the night before last, we have been in valleys, surrounded by mountains. I have enough geographic nous to realise that since we are following a river we are prone to the more vertical features that we have thus far encountered, but I had thought that Tibet might reveal a little more of itself to us and open up. As we progressed that afternoon the valley did widen in stretches, but it never broke into plateau. Maybe tomorrow.

In the evening it was another dip in a freezing stream to cleanse body and mind. I might believe myself to be hardy, to be able to endure such temperatures, inured to such exposure, but I can only do so for short stretches at a time. The mind boggles at the Victorian Puritanism of the likes of Francis Younghusband who used to take pleasure from bathing daily in such icy cold water – “I am not cut out to be a Victorian explorer,” I said to Ian, equally uncomfortable in the cold as I was. After such ‘refreshing’ cold, we sought warmth in various layers of clothing, the lukewarm delights of packet noodles and then the welcoming embrace of our sleeping bags.

*

Foul weather, windy, cold and sleeting, greeted us at dawn, consequently it was an easy decision to remain in the tent and to try to catch up with our diaries and listen to the news on the radio. “Did you hear that? NATO mistakenly bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade because they had been using old, out of date maps!” said Ian. I noted with some irony that whilst Ian was telling me this he was poring over our equally ancient US map of Tibet - fortunately we do not have to be quiet as accurate as the NATO bombers.

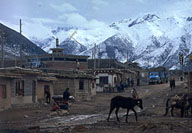

When the wind and sleet had calmed, we got on our way and were graced with scenery that matched my preconceived ideas of Tibet. Wide plains gave the panorama a breadth and width, a feel of size that was heightened by the big skies. The scenery itself was desolate and harsh, windswept, colour blasted from the terrain by exposure to the elements. The browns and greens were washed out, the distant summits tinged with a recent sprinkling of snow. There was a definite severity to the landscape, but at the same time an austere beauty. It was the fierce savageness of the plains, an extreme that forced eyes to be screwed up against the harshness and the brightness of the light.

But with this expanse and scale of vista came the wind. A wind that was relentless, impeding and buffeting two hapless cyclists, a wind whose strength shaped and scarred the landscape as well as our faces - many of the stone mileage markers by the side of the road had had their numbers worn away by the force of the wind. Blowing and blasting around my ears, the wind seemed to lock me in my own cocoon, unable to hear or communicate. As I wrote in my diary, “it was an isolation that served to accentuate the vastness of the landscape around me”.

The wind was a struggle, but we simply had to get our heads down, grin

and bear it, and keep cycling no matter how slowly. Windbeaten, in more

sense than one, after a tortuous sixty-nine kilometres we pitched camp

in a wide, wonderfully quiet and isolated valley. As we watched the dzu

gently grazing in the warm afternoon sun, the respite from the wind was

blissful, the silence loud and powerful in contrast to the roar of the

wind. I felt shell-shocked and the sheer scale of the surrounds imbued

me with a feeling of the power of nature, its timelessness. My imagination

and inner self were profoundly stirred by the immensity around me. My

ears still ringing, I felt a strange empathy with the Tibetan nomads,

the North American Indians of the high plateau, people at one with their

habitat, believing not in one single deity, but the force of nature and

a host of spirits. I felt belittled, literally in awe.

|

|

|