Chapter 2 - Cambodia

Cambodia is a country seeking stability after many years of turmoil and trauma. It is a country that is not at ease with itself and is struggling to find an identity. This uneasiness is infectious, and it rubbed off on me, making me feel slightly apprehensive. I was invaded by worries about travelling in Cambodia, worries that were exacerbated by the doubts and opinions of many in Vietnam. The Vietnamese have no real love for the Khmer, viewing lawless Cambodia with mistrust and not venturing across the border.

There was some positive and upbeat reaction to the situation in Cambodia. Overhearing a conversation between an Australian travel agent and his Vietnamese counterpart, I gleaned that Cambodia is to be featured in a number of large airlines’ travel brochures next year - a seal of approval, a sure sign of more settled times. Yet this view was not absolute, the general reaction being one of caution. Most advised us to take heed, to keep our ears close to the ground and take no risks. One extreme view was of the typically paranoid American expatriate was not to go at all, “Hell, its like the Wild West over there.” Graham Greene was so right about the Americans in ‘The Quiet American’.

Forewarned and with every intention of treading carefully, we took heart in the reassurance of the matronly receptionist at the Cambodian consulate in HCM.

“You go. No problem. Cambodia safe.”

“It's not so much me that is worried but my mother.”

“I tell your mother all OK.”

Taking her at her word, we found ourselves at the border the next day. Land border crossings are invariably complicated by bits of paper, not having bits of paper and by bored self-important officials who become uptight by the casual attitude of people like Ian and I to such bureaucracy.

“Where paper?” barked an officious customs officer.

“I don't have it.”

“Where Yellow Paper.” he tried to clarify, speaking deliberately and slowly.

“They took it at Ho Chi Minh airport when I arrived.”

“No,” a refusal to believe that his fellow officers could have made such a mistake.

“The customs took it at the airport.”

The disgruntled official read from my form how one is required to submit this form to the customs officer upon exiting Vietnam. Satisfied that this had shed new light on the trouble and made everything clear, that the blame for not having the form did not lie with his colleagues in HCM but with Ian, he shook his head and smugly ordered, “Back to Ho Chi Minh.”

Do not pass go. Do not collect £200. Go straight to jail. Was the game over before it had begun? A heartbeat was missed. Ian’s face flushed as he contemplated whether or not to play his ‘get out of jail free’ card: the greenback. Feet were shuffled awkwardly, as if to free ankles from some mysterious grasp. A pause, an expectant pause, waiting. The official looked around, furtively checking that the coast was clear and begrudgingly grunted, “Go.” And go we did, before a change of mind or the arrival of a more senior officer.

Walking under the once proud archway that denoted the border between Vietnam and Cambodia the change was stark, the contrast between the two immediate. The Cambodian officials were more informal. They were happy and smiling as if they were actually glad to see new faces crossing the border. They were housed not in a self-important concrete building but a ramshackle hut and formalities here were uncomplicated and hassle free.

The border, more than a line drawn up on a map, changed everything. The state of the road was in disrepair. Pot-holed and uneven, it was hard to drive along, hard on the suspension and hardy on the passenger. And this was Road No 1 - heavens help the other roads. The fields were not cultivated and tended to the same extent, or with the same meticulousness, as in Vietnam. Space lay redundant, water stagnant and filthy. Litter crowded and dirtied the roadside, mangy dogs that resembled hyenas nosed through the refuse. Even the people were not as well turned out as the Vietnamese, clothes more ragged with not the same attention to detail. The neat well-made conical hats replaced by kramas that look to me like tea towels wrapped loosely around the head. The change in fortune, the poverty delineated by the border was striking, even the green of the fields was a poorer duller green.

The sky compensated for any deficit in the land. It was big, the horizon wide. A feeling of space pervaded that was almost overwhelming, an open landscape not filled by the order and development of across the border. The population of Cambodia is only 10 million; there are almost that many people in HCM alone. This much lower population density allows for a more lax, less fastidious management of the land. The Cambodians do not seem to be as industrious as their Vietnamese neighbours, the premium on space not as great and hence the land is not cultivated to the same extent giving me the initial impression of a lack of development.

First impressions last and still today in my mind the memory abounds that Cambodia is scruffier than Vietnam. That might be so, but my initial reasoning behind the difference was wrong. A few days later I was talking to a Cambodian man about the harvests and the seemingly unproductive nature of the land. He told me that at best there were two harvests a year, normally only one, whereas in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam they are fortunate to have two harvests as a norm and three harvests in a very good year. This year due to the lack of rains there was to be only one harvest in Cambodia, the failing harvest replaced by outside food donations and parcels, making this already poor country further indebted to the United Nations and the First World.

Despite this poverty, the houses, some raised on stilts to protect against the rising waters of the Mekong, others on the ground left to the mercy of the floods, have an air, albeit an assumed false air, of wealth. Surrounded by water, a grass path breaking their splendid isolationism, these houses stand back from the roadside, cloaked in trees (eucalyptus that is rarely seen in Vietnam) with the feel of a villa about them. The blaze of colour bestowed by the bougainvillaea adds to this villa image.

The pools of water that surround every home in the Cambodian countryside are known as trapeang. These pools, which fill up and dry out according to the seasons, show that the Cambodians, like everyone else, are dependent for survival on a constant source of water, used not just in the home but also to irrigate the land. As we were to discover at Angkor Wat the vital role of water in Khmer society has huge symbolism and association, namely in the form of a snake or naga.

The wide streets, avenues even, of Phnom Penh sounded and seemed empty after the bustle of Ho Chi Minh traffic. Spacious and relatively empty the streets had an autocratic, totalitarian feel to them, and yet the people seemed happy, relaxed in the slowness of Sunday. Families picnicked idly along the river, couples enjoyed a shared moment. Kids rode miniature boats, cars and fighter planes on a merry-go-round that has been deprived of paint for years. Vendors touted colourful balloons. Scenes of a lazy carefree weekend.

I enjoyed such scenes, but in the back of my mind I could not forget Year Zero and hence, for me, there was an almost eerie feel to Phnom Penh. My initial impressions were undoubtedly prejudiced by prior knowledge and what I had read of the horrors of the Khmer Rouge regime. Our minds are never entirely blank or neutral; we are burdened by preconceptions, tainted by association. Maybe I should have tried to appreciate the calm and order of Phnom Penh rather than subjecting it to images of the past. I should have taken the city for what it is and has become, not for what it was. Yet it is not easy to forget. We can forgive but cannot forget, there will always be that mental scar, that taint and the slant.

Saddened by such thoughts we sought solace in the comforts of a small friendly hotel. Out of character, I picked up the hotel regulations and began reading. “Regulation 1. We would like you to fill in the application form in the hotel and pay before checking out.” Fair enough I thought to myself. “Regulation 2. All kinds of explosive devices are not allowed to be brought into the hotel.” This all too clearly reflected Cambodia's recent troubles, its unease and the suspicion that still lingers. Needless to say it did little to lighten my frame of mind.

*

History books record that one to three million people died from execution, overwork and starvation during the three years and eight months in which the Khmer Rouge ruled Cambodia in the late 1970s. At least one fifth of the Cambodian population was killed. During this time, Cambodians were forced at gunpoint into rural communes to build the Khmer Rouge dream of a collective, agrarian society. Pol Pot and his regime tried to turn back the clock by emptying all the towns and cities. Pol Pot’s real name was Saloth Sar and I agree with Carol Livingstone when she states in her book ‘Gecko Tails’ that “The name Pol Pot is a fiction, a meaningless Khmer name designed to imbue Saloth Sar with mystery and power and hide the truth. Saloth Sar doesn’t deserve such mystery and power.”

Year Zero, as it was known, was one of the most brutal and terrible restructurings of society ever attempted. It was an attempt to remove all differences between townspeople and peasants by the destruction of the centres of mercantile and capitalist activity. The whole population was moved to the countryside. Money and private property were abolished, temples and schools were shut down, and almost all contact with the outside world was severed. Hundreds and thousands of Cambodians, including intellectuals, graduates, professionals, those who spoke foreign languages and even those who wore glasses, were branded as subversive or parasites and were tortured and executed in torture camps around the country. The hunger of the people was such that it was debilitating to the point of insanity. People cooked and ate non-poisonous grass like it was a vegetable. Some are said to have been so hungry that they dug up dead bodies, slit the flesh and fried it.

It is difficult to come to terms with such tragedy, especially as many of the Khmer leaders were, and still are, extremely bright and able, Pol Pot himself studying in France. We were told of how one KR leader had been seen in the Ministry of the Interior a couple of weeks ago writing with both hands, i.e. holding a pen in each hand. Not only that but he was writing simultaneously in different languages. The mind boggles at such intelligence, its potential and how it could be so misused.

The Killing Fields at Choueng-Ek, just outside Phnom Penh, were where many were murdered. The Killing Fields were made infamous by Sydney Schanberg, then a New York Times reporter, who worked with Dith Pran, a photographer and Cambodian activist, to expose the atrocities of Pol Pot and his regime. The film of the same name also did much to expose future generations to the horrors of the Khmer Rouge years. Sadly, an Asian street gang in Los Angeles murdered Haing Nor who played Dith Pran in the film and was himself a survivor of the Killing Fields in 1986.

17,000 people were killed at Choueng-Ek between 1975-1978. The remains of 8,985 people, many bound and blindfolded, have been exhumed. 43 of the 129 communal graves have been left untouched. The majority of those killed were bludgeoned to death, clubbed, hacked, beaten rather than shot, as the Khmer Rouge were trying to save precious bullets. The slaughter, especially the brutal means in order to preserve ammunition, is incomprehensible and I am left feeling hollow, questioning in shock. A memorial built in 1983 houses some sixteen levels, each crammed with skulls, each level containing seventeen by seventeen skulls. Hollow empty skulls, fractured and broken, that stare from dark sockets in silence. Grassed over pits with bleak signs inform that “450 women ad children are buried here.”

The torture chambers of Tuol Seng are a profoundly depressing experience. There is something about the sheer ordinariness of the place that made me shudder. The suburban setting, the plain school building and the grassy playground make it all the more sinister. In 1975 the Tuol Seng High School was turned into Security Prison 21, the largest detention centre in the country. 17,000 people were tortured and killed here, and in early 1977 S21 was claiming one hundred victims a day. When the Vietnamese liberated Phnom Penh in early 1979 only seven prisoners were found alive. Fourteen others were tortured to death as the Vietnamese forces were closing in on the city, their graves stand tragically in the courtyard.

Tuol Seng is humanity at its worst and the images are stark, grim and tangible. Too tangible, as I was punched in the stomach, sent reeling by the awfulness that surrounded me. Punched again and again, continuously. Blood drained from my face as it whitened. My fingers trembled with pity, anger, grief. Deep breaths. I had to take deep breaths, to suck in the air. I tried to be calm, to be objective, but the visual evidence was unrelenting and overwhelming. Bare, rusted iron beds stood as silent witnesses on chequered floors. Shackles and iron posts fixed to the floor were brutal evidence of torture, spots of blood the result. Cold metal ammunition boxes used for defecation. It was sickening. A single black and white photo of the battered victim filled the cell with an immediacy, a horrible testament that it was so very real, that it did happen. Faint and light-hearted I staggered to the next cell to be confronted by similar grimness. It was never ending and yet there is more, much more that is not open, that is hidden from view, as the second and third floors are closed to the public (some say because they implicate those currently in power, that the evidence is too close to home).

Photos, hundreds of photos, of faces staring, bewildered, anguished, confused. The walls stared with fearful, saddening memories. Bloodied faces, strangled necks, young, old, children, women, numbers pinned to their garments, their eyes accusing and frightened. It is impossible to try to understand, to understand why they wanted to record it all in such morbid detail. It is harrowing, but perhaps worst of all were the photos of the deserted streets of Phnom Penh. Streets that were devoid of life, cold and unhearing to the anguished cries from within Tuol Seng. It was both sobering and savage to see the city so lifeless, the whole population moved out to the countryside.

Shell-shocked and reeling, I had to shake my head

vigorously to try to rid my mind of such terrible images. They are

horrific and catastrophic

not least for the magnitude and extent of such terror. Hardly a family

was not affected and most Cambodians have to live with this terrible

past, unable to forget with the shake of the head. Having lunch with

a delightful Cambodian family the aunt pointed to her niece and said, “Her

father killed” as she slid her finger across her throat. “Her

uncle too. He and many others were made to lie on the ground and were

then run over by a tank.”

This family like so many others lost everything – possessions,

loved ones, happiness, and any sense of normality. “Couples were

forced to marry. One of my brothers and one of my sisters are not my

real brothers or sisters, only half. My mother, they forced her to

marry and have two children. Only afterwards could she get a divorce.” Seeing

our incredulous faces she says with remarkable candour, “It is

in the past. I know it happened. OK now.”

‘OK now’? How can it be OK now after what they have endured? I am in awe of this ability the Cambodians have to put the Pol Pot era behind them. I admire their phlegmatic stoicism, their resilience and their unmoving resolve despite what has happened to live as normal a life as possible. The Cambodians have a remarkable capacity for acceptance, so much so that there are stories of Khmer Rouge officers, known torturers and murderers returning to their villages and being accepted. But perhaps such acceptance is not totally positive, perhaps it was one of the reasons that the regime was able to get away with what it did.

A controversial topic at best and after the emotional drain of Tuol Seng perhaps too disturbing to contemplate. Rather than be confrontational we went to seek out liquid refreshment, to dull the grey matter and try to forget the enormity of what we had just seen. Refuge was found in the ‘Happy Herb Bistro’ which offered free joints with the beer. I declined the joint preferring the calming atmosphere, the setting sun and the palm trees lining the banks of the Tongle Sap.

The spirit of a couple of kids in Motivation wheelchairs restored my faith in humankind. They crowded around David, fascinated by his wheelchair, bargaining hard for it and trying to get David to swap. David in his usual good humoured manner played along, proud to see the independence and confidence that their wheelchairs gave to the boys. One of them was a young fifteen-year-old boy, who looked more like seven, with no arms and no legs. Yet despite the cruel hand that fate had dealt him he had amazing gaiety and spirit. He was plucky and his courage touched us all.

*

Phnom Penh is congested with NGO (Non Governmental Organisation) vehicles, from the peripatetic white Land Cruisers of the UN to those of Handicap International, from mine clearance to childcare they are all here. The coming of the UN in the early 1990s, some 26,000 officials and troops, was like a goldrush to this otherwise destitute city. It led to a massive influx of money, tourists and investment. Restaurants were opened, hotels were hastily constructed, it was manna from heaven. Far be it for me to decry much of the wonderful work that has been accomplished, but the advent of so much money has had its downside. There are the negative aspects of profiteering, begging and inflated prices.

Yet the massive clearance of mines that has taken place in the country must more than outweigh any negative points associated with such a foreign presence of aid workers. At present there are 4,000 people employed in the clearance of mines in Cambodia. Last year in 1998 120 people were wounded every months from mines, but due to much of the good work that has taken place that figure has fallen to 60 people month.

Cambodia is littered with some four to eight million mines, and over 35,000 Cambodians have lost limbs due to mines. This is the highest per capita rate of amputees in the world and thus after malaria and tuberculosis, mines are Cambodia's biggest killer. The cost to the country is massive, not only in terms of the physically injured but also economically. The UN reckon that the rehabilitation cost of each land mine victim is $3,000, but then you have to take into account other factors such as the loss of livestock and the loss of cultivable land. It is a tragic situation and one that is very real - when walking around the countryside it is necessary to take care. Several times I was conscious of the fact that my next step could be my last.

With so many amputees the work of organisations such as Motivation are invaluable to the rebuilding of Cambodia and its confidence. Motivation not only provides wheelchairs in self-sustaining projects but also actively seeks to enhance the quality of life of wheelchair users. Thus one of the reasons that David came back to the region with Ian and I was to visit and evaluate the success of the Mekong Wheelchair Project. He wanted to do a quality of life study, to assess the benefits of Motivation wheelchairs and whether they have helped individuals to achieve their maximum potential. Ian and I were privileged to be able to join David on his return to the workshop six years after setting up the initial project.

Long lost friends returning, David was greeted with genuine feeling, big smiles and joyous eyes. I was impressed with the warmth of his reception. David himself was also obviously glad to be back, to be with old friends, to reminisce. Even the directness of one frank greeting, “Mr David so good to see you. You fatter,” did not dampen his delight at returning.

We were taken on a tour of the workshop. The workshop itself is impressive in its industry with an output of some eight hundred wheelchairs every year. The seventeen workers are all amputees, their upper bodies hardened from years in a wheelchair, their stumps twitching involuntarily below the knee. They are hardworking and thorough and derive a huge amount of satisfaction from their work, which is obvious in our warm welcome. The wheelchairs are constructed on site. All the parts are made locally, thus keeping down costs and ensuring that parts can be replaced.

The Mekong Wheelchair Project is housed in the grounds of the Jesuit Refugee Service, which maintain the day to day running of the project. The site was formerly a prison, but now has a much happier atmosphere, a feel of community and belonging, with some eighty 'students' living on the campus, most of them disabled in one way or another by mines. I say students because that is what they are, learning how to readjust to society, developing skills that will enable them to contribute to village life in a positive way. They are a variety of ages, mines do not discriminate.

In the grounds there is a touching tribute to Brother Richard M. Fernando, who on 17 October 1997 sacrificed his life to save that of a pupil and the rest of the class. A disturbed student suddenly produced a grenade in the middle of a class and pulled the pin. Brother Richard grabbed the boy, seized the grenade and shielded everyone in the room from the blast. A sad incident that reveals the unsettled nature of many of the students, how necessary the work of the centre is and the dedication of the Jesuits, that one was prepared to make the ultimate sacrifice.

In the afternoon it was out on the road to meet some of the beneficiaries of the project. David was interested to see if their chairs were providing them with a better standard of life, and if the chairs themselves were standing up to the punishment of village life. First stop was the house of Vanna, a seventeen-year-old boy who had had polio since birth. His chair had provided him with independence and freedom, enabled him to travel to school (he had completed five courses which according to Paxti, a young Jesuit priest, was good for Cambodia). He was clearly very happy with his chair. But there was a problem with the front wheel, the bearings had rusted due to the fact that when washing or collecting water the wheel is immersed. The team were concerned, asking questions and discussing ways in which the design could be improved, what they could do to help.

David himself was subject to much scrutiny. It is great that he visits these villages, meets other wheelchair users, showing what can be done, that despite a disability a happy productive life can be led. Vanna’s father was intrigued, trying to come to terms with a paralysis below the neck, feeling, pressing, and holding David’s hands with touching concern. The warmth and the intimacy of the moment moved me.

Then on to the next village and Suret, a young boy with cerebral palsy who could not speak but seemed to understand and recognise. His chair was like a deck chair on wheels, not ideal for a child with cerebral palsy as I was to learn - they should be upright, given as much support as possible, strapped in so that energy is not wasted on trying to move, but trying to communicate. The team commented that the chair was far from perfect, but given the circumstances and resources it was adequate. At least it gave Suret the opportunity of being moved about and taken for walks, which he clearly enjoyed. In Cambodia there are more pressing demands and the likes of Suret are low down on the list.

Despite such problems the team battles on, its spirit encapsulated by the infectious laughter of Savanna, who heads up the distribution of chairs in Cambodia. He travels the country, monitors the progress of wheelchair users, his easygoing happy nature creating bonds and trust in a country plagued by self-doubt, his giggles breaking the ice. Savanna, the Mickey Mouse of Cambodia, his ears inordinately large for the size of his smiling face, has a magical light-hearted touch that is approachable and warm. He brings happiness and hope to many. This is what Motivation does.

*

The Krousar Thmey School for the deaf and blind where Pungya works is modest, yet neat and tidy, impressive in its achievements. Pungya, proud of the school, met us with open arms and wonderful smile, eyes sparkling with the thrill of being able to show off her hard work.

“As with many handicaps in the developing world deafness is looked down upon, misunderstood and children ostracised. Cambodia is no different,” she says sadly.

“The school was set up to help the children acquire self-confidence and integrate them back into society.”

“Is that difficult?”

“At first, yes. Many parents were not interested and could not afford to invest either time or effort into their kids. Some are even too poor to care for their kids and for this reason the school is not a boarding, or else many of them would be abandoned here.”

“But how can the parents afford to pay now, does the government help?”

“There are some seventy children at the school now, and they are funded mainly by the French, all lessons, materials and uniforms are paid for. The kids, they are great kids, are taught not only sign language but also normal studies maths, grammar, music and dance.”

Music and dance are not two subjects that I would have associated with a deaf and dumb school, but there again I had no idea how the deaf and the blind communicated to each other.

“They sign on each others hands,” was Pungya's answer. It was fascinating and touching to watch their silent, patient communications. Fingers deftly conveying messages, faces expressing the joy of these exchanges. I wondered whether they could enjoy such communication at home, outside the security of the school.

“Most of the parents are happy, so proud of what their children have learnt here,” says Pungya smiling broadly, looking fondly at a group playing happily together. “Most will learn the basics of sign language. There is one father, a father of two twin girls, who takes a real pride and delight in his daughters, their dress and development.”

This is all the more remarkable, because not only are they deaf, but they are girls - Khmer society is still very much male dominated, the female subservient. But perhaps it is a reflection of today's parents in Cambodia. They are a generation who had nothing, everything was taken away from them, and they want their children’s lives and experiences to be different. Today’s Cambodian parents want their children to have what they never had.

Pungya had been busy helping to organise a show for the imminent visit of a government official to the school. She was eager to show us the rehearsal, we both equally keen to see it. The rehearsal was taking place in a large upstairs room, light and airy with bare walls, it assumed the air of a simple dance hall. At the far end of the room were the blind children, the musicians. The dancers, the deaf children, filed in on cue from a teacher and began a traditional Khmer dance, ‘the butterfly dance’ as Pungya called it. During their dance the deaf children were guided by the teacher and aided by two large mirrors in which they were able to watch each other’s timing. They were also able to feel, and thus were prompted by, the vibrations on the wooden floorboards. Their faces creased in concentration showed how desparate they were to please. The smiles and twinkle in the eyes betrayed their nervous excitement. It was obvious and pleasing to see how much enjoyment they derived from their performances as they danced, played the xylophone and crashed symbols. And what is more, they were good.

Outside the children were boisterous, jumping and waving their arms about in excitement, broad smiles creasing their faces. It was mayhem as they all vied for attention, the short moaning and groaning of attempted speech. Hands would be pulled down the side of a face, indicating that I had a long face. Noses pulled referring to my large nose. Hands and legs waved awkwardly in the air meaning that I was tall and gangly - either I was a natural at sign language or I really am a tall, big-nosed and gangly. I think the answer is obvious. They were brutally frank in their appraisal of me, it was like a character assassination or rather a physical appearance assassination, my one redeeming feature seemed to be strength, flexing of biceps.

The quiet simplicity of their communication, the white smiles, the jumping up and down on the same spot all revealed all too clearly how happy they were. Pungya talked animatedly about her charges, about how she was trying to produce a Khmer sign language book, a first, and about the dancing and music. She was proud and had every reason to be so.

*

Fans rotating in idle silence, wooden chairs with leather cushions, the distant clicking of billiard balls, a balcony overlooking the palm trees alongside the river are part of the charms of the Foreign Correspondents Club. It is a lazy world removed from the commotion below and we enjoyed our sundowners. I was lost in reverie and contemplation of the road ahead when suddenly I saw an elephant walking down the street. A cartoon double take and a quick glance at my beer to see how much I had had and the elephant was still there. “Did you see that elephant,” I said to Ian seeking reassurance that I was not just imagining things. It was a surreal moment that seemed to fit into the romantic charm of being in the Foreign Correspondents Club. However the reality of the elephant being on the streets was not as romantic as I might have imagined for it is used to walk tourists around Wat Phnom. Although the story of the elephant and its keeper is touching: local legend states that the elephant's tender is unmarried because the elephant will not allow it. They are inseparable. Now that is a real crush that reveals the power of pachyderm passion.

*

The next morning we travelled to Angkor Wat by ‘express boat’ that takes some five hours, costs $25 and led to a loss of hearing, as the roar of the diesel engines is not dissimilar to an Inter-city 125 train. Not content with the volume of noise generated by the engines, the Cambodians and the Chinese sat inside a gloomy cabin of frosted glass windows subjecting their eardrums to a video of ear-splitting violence. Backpackers meanwhile chose to soak up the atmosphere and spray by sitting on the roof and watching life whiz by. And it did whiz by as the boat lived up to its title of express and created a massive wash that violently rocked and disrupted the tranquil calm of the fishermen. Determined to keep to schedule the boat did not deign to slow down when passing lone anglers in their small wooden boats, preferring to soak them in spray and engulf the boat in wash rather than miss its deadline. I am certain that none of the profits from this lucrative express boat compensate sodden fishermen or goes to make amends for the erosion of the banks caused by the wash.

Our destination was the Northwest corner of the Tongle Sap, a large lake linked to the Mekong by a hundred kilometre channel. During the rainy season from May to early October the Mekong rises forcing the Tongle Sap to flow north-west into the lake and thus flooding the lake, transforming it from 3000 square kilometres to 7500 square kilometres. With the onset of the dry season the water level falls, draining the waters of the lake back into the Mekong - the Mekong must surely be the only river in the world that flows both ways. This extraordinary process results in fertile well-irrigated land surrounding the lake.

On arrival our champion of speed was swamped by a swarm of smaller boats that had come to take us on the next leg of our journey, the river being too narrow for any form of express transport. Like fish fighting for bread, the waters erupted in a frenzy of splashing as these boats came alongside trying to encourage the unsuspecting and the unprepared to a “very good, very cheap hotel”. Those forewarned, such as ourselves, and with the foresight to book ahead were not exempt from attention. Pieces of paper bearing names of passengers were thrust in our faces as we tried in vain to find our names. As pandemonium breaks out and boats tilt precariously, we pushed and shoved through the melee of paper and muted voices (ears are still suffering the effects of the engine) trying to find our names. More pushing and shoving and then a sense of relief as we found our man, a smiled greeting and a sense of calm.

We transferred to the smaller boat and began a diesel-juddering journey of sedate progress through the narrow river, some twenty metres across. The river is cramped and convoluted, houseboats on the tow, it is teeming with fishermen. The fishermen, their lean bodies, golden and glittering in the water, well toned from years of fishing, employ a variety of tactics. Some throw weighted nets, others use cane cages, nets on the end of a wooden paddle are used as a scoop, nets on wooden frames are lowered into the water. Some fishermen wait patiently in boats whilst others feel the river floor with their feet for signs of life. Some slap the water to scare the fish, others probe the riverside undergrowth with sticks. With this wealth of rudimentary tactics the fish have little chance of survival, let alone peaceful existence, hassled and harried constantly. With all this activity I would have thought that fish is plentiful and cheap in the markets, but I am corrected by Sopia our name-bearing friend and now guide by default. He informs me that fish is expensive at 5,000 Riel per kilo (approximately $1.30) because commercial companies exporting to Thailand exploit the Tongle Sap leaving little for the fishermen and the markets.

The end of the river brought a tricky process of disembarkation. Any slip would have resulted in an unpleasant dip in the stinking squalor of the black debris-littered water. This fishing village is poor, maybe as a direct result of the commercial exploitation of the Tongle Sap, existing in appalling conditions of stagnant rot. And yet a few minutes moped ride brought us into a very different world. The road is shaded, crowded with trees mainly palm, with a sleepy content feel to it. The houses are on stilts but no longer ramshackle and dishevelled, but sturdy and well built with big strong timber. A stream flows alongside the road, a water wheel turns slowly, children cycle in uniform, not sitting around naked and aimless. The contrast is great. I try to fathom out why this is so, because they are farmers, because they have benefited from the slow trickle of tourists? Perhaps it is simply the difference between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’. A young boy cycles pat, his bicycle too big for him to reach the pedals so he sits in the crossbar. Uncomfortable but at least he has got a bicycle.

After a marathon journey we arrived in Srim Reap. Srim Reap is the nearest town and staging post from which to visit Angkor, the ancient Khmer civilisation of Cambodia. Before coming here I had thought that Angkor consisted solely of Angkor Wat, but I could not have been more wrong as Angkor consists not of one but of one hundred monuments, including two dozen temples. The amazing architectural wealth that the ancient Khmers left us is a truly incredible legacy. Angkor Wat is an impressive temple in its own right, but as a complex, the temples of Angkor more than rival anything else I have ever seen and must surely be one of the wonders of the world. Yet we know so little of these marvels in the jungle of northern Cambodia.

Knowing where to start and picking and choosing from such a wealth of choices is not easy. We made the decision easier by employing the services of Sopia and Cook, and their trusty motorbikes. Sopia with his warm smile, floppy hat and girl at every temple seemed a bargain at $8 per day. As his bike spluttered to life, Sopia began feeding me with facts and figures about Angkor Wat, “Angkor means royal palace and ‘Wat’ temple and it was built in the reign of Surjavarman II (1112-1152).”

The reign of Surjavarman was a time when the Angkor empire, 802-1431, was reaching its cultural and architectural zenith. As a result Angkor Wat is the largest and grandest of the one hundred or so temples within the region. A moat that is just under 200 metres wide surrounds the temple complex. The temple walls within are over one kilometre long, its main tower is 50 metres above the ground - it is the largest temple in the world with a volume of stone equal to that of the Great Pyramid, the pyramid of Kheops, in Giza. But all the above are just statistics, statistics that armed me with knowledge, prepared me to think big, of what to expect, but that in actual fact were meaningless when I was confronted with the enormity of seeing Angkor for the first time.

Sopia’s motorbike was suddenly free from the claustrophobic ringing of the jungle and there before me stood Angkor Wat. “This Angkor,” said Sopia drifting off into a little spiel about the site, but I did not hear him. I was overwhelmed by an impression of size and space, the expanses stretching before me creating a feeling of power. A power heightened not only by the scale of the building but also in the arresting of the encroachment of the jungle. It was not the height that was impressive, although once inside I realised that it was deceptively high, but the width. It is its width that confers upon Angkor Wat a feeling of the monumental, the width impresses with a sense of regal majesty and wealth.

Outside the moat hordes of women and children tried to make me part with my money for a selection of T-shirts, flutes, scarves, cars carefully constructed from cans of coke and cold drinks. “Sir, Sir. Wanna cold drink?” Their banter is light-hearted, not the hard sell of some of the world's more frequented tourist sights. With indifferent irreverence kids play toss the flip-flop, seemingly a lighter, more plastic version of horseshoes. Amputees drag themselves along, hand outstretched, limbs absent or hideously disfigured by the blast of mines.

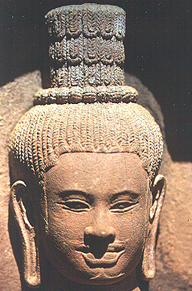

Crossing the moat I felt as though I was escaping the poverty of today, stepping back in time to a world of magnificent splendour. My mood was immediately lightened by the lively cohorts of female divinities, asparas. Their flirtatious movement is soothing, their flowing dance gay and sprightly. Sumptuous heavy head-dresses, waving skirts and well-rounded breasts enrapture. Carved with coquettish care they bring the walls to life, the shade and light playing alternately on their impassionate faces.

From the Western Wall to the base of the actual pyramid one has to follow a raised causeway and again I am filled with thoughts of processions, pomp and ceremony, adding to the splendour of the site. Chanting and colour fill my mind as I try to imagine the original magnificence. The 500 metre long causeway is flanked at its halfway point by a ruin of a library, further beyond the temple itself, its towers rising mysteriously like grey fir cones from the colonnade below. Palm trees break the horizon, their bright green in stark contrast to the worn grey of the temple and its blackened roofs. The weathered sandstone is imbued with imperial decadence, the darkened rooftops and the crumbling towers are far more romantic and evocative than the new and retouched.

The colonnade protects walls covered in fine, beautiful bas-reliefs from the weathering rays of the sun, but does not protect against the hands of homage, hands that have touched the relief in awe of its carving, hands that have smoothed the bas-reliefs giving an impression of black marble. The reliefs depict a variety of scenes from legend, from religion, to the military victories of Surjavarman II. They are as epic as the battles they are portraying. On one half of one wall I counted over seven hundred foot-high soldiers on the bottom tier alone (forgive me if this figure is wrong but it is difficult in the heat and confusion of battle to be certain).

*

“You late. You late. You drink beer last night,” chirped Sopia happily.

I could not understand how Sopia could be so chirpy - it was early in the morning, so early that it was still dark. We were not hungover, just unaccustomed to being awake at such an hour. We had awoken at this unnatural hour to see Angkor Thom in the early morning light.

As we crossed the moat, entering Angkor Thom through one of its four impressive gates I questioned the wisdom of this decision. 54 devils on one side and 54 gods on the other line the bridge spanning the moat, yet I found it difficult to distinguish between the two. I was uncertain whether this was due to the uncertain light of pre-dawn, or my inability to distinguish between right and wrong or due to the worn, weather-beaten state of many of the faces. Although losing their shape, the faces here on the South Gate were better preserved than on the other gates where unfortunately the years have not been so kind and recently they have been prey to vandalism and theft. “One head sell for $20,000,” Sopia reliably informed me.

The Bayon, for me the most enchanting sight within Angkor Thom, is mystical. Its shapelessness shrouds it in a mystery that is only revealed on closer inspection. From a distance I see piles of crumbling formless stone and it is only when I get closer that I can distinguish faces, and only once I get amongst the faces do they spring eerily to life.

The Bayon is enchanting, especially at dawn, when the morning sun casts light on the faces revealing a little of their mysticism. They remain impenetrable, staring stonily ahead, omnipresent and all seeing. Countless towers of faces watching my every move, wherever I turn I cannot avoid their bewitching gaze. Silent, a metre and a half high, face on, in profile, perfectly preserved, crumbling, sprouting green facial hair, they turn ashen and harsh in the midday sun, warmer and fuller in the softer focus of dusk. It is not just me that is intrigued by their enthralling silence, as for years archaeologists and historians have tried to fathom their symbolic meaning. But they will not spill their secrets, they will continue to enchant.

The air is still, sounds of stirring life from within the jungle. The howling of monkeys, chirping of bats and chanting of birds, and yet there is an eerie silence within the Bayon itself as the golden orb slowly rises. The cold stillness of aged stone contrasts with the noisy chatter of the young jungle.

I regard myself as phlegmatic, immune to the passions of religion, but amongst these faces, so many faces, there is an almost spiritual feel. A mysterious, enigmatic air pervades that stirs the soul, that one cannot fail to be moved by. Even the noisy staccato shouts of the groups of tourists cannot break the magic. There is a feeling of power, not a physical power as at Angkor Wat, but a mental power.

Whilst the upper echelons of the Bayon are enshrouded in exoticism, the base is more down to earth, more tangible due to the earthiness of its bas-reliefs. What they lack in terms of precision and detail compared to Angkor Wat they more than make up for in terms of spirit and character. Scenes of everyday life are not only illuminating historically but do not leave me detached, instead inviting me to share in their pleasures. Of course there are the obligatory battle scenes but description of the epic gives way to wrestling, acrobatics, playing chess and cock fighting, a pig on a spit, feasting, drunkenness and revelry. Yet it is the attention to detail, not of the art itself but of everyday life, that I find so appealing: a piglet suckling from his mother, a dog scratching his ear with his hind leg.

Although down to earth, the bas-reliefs of the Bayon also speak of the greatness of the Angkor kingdom and king Jayavarman II. The Khmer are portrayed with elongated ear lobes, one of the many symbols for portraying Buddha, the enlightened one. The whole complex of Angkor Thom revels in the magnificence of wealth and the display of power, such as the Elephant Terrace which conjures up scenes of military parades and fanfares, a triumph of colours, elephants plodding past and soldiers marching in file. The Baphoun, yet another feature in the massive complex of Angkor Thom, though under restoration, allows our imaginations to run riot and invests a mysticism in its pyramidal representation of Mt Meru, the centre and axis of the universe in Indian cosmology.

Angkor Thom must have done much to reassure Jayavarman of his immortality. A forgotten king passes into oblivion but not Jayavarman whose cult is still visited today, albeit by a very different subject from that which he might have imagined. After only ten years of his reign, Jayavarman had some 13,000 villages, a population of over 300,000, working on his projects, whose only function was the furtherance of his cult. Jayavarman’s reign left us much to appreciate – it is said that he built more in his reign than all his predecessors taken together – but it foreshadowed the end of the Angkor Empire. Indeed not one great monument was built after his reign for he had drained the Khmer civilisation of all energy and resources.

Back on the bike Sopia chatted animatedly about his country. He pointed out artillery pieces lying derelict in the undergrowth, remnants of scuffles between the Khmer Rouge and the army. I enjoyed his frankness, his wish to talk, but unfortunately took much of what he said with a pinch of salt - well, he did think that I looked like Leonardo di Caprio. A screech of brakes and we arrived, “Ta Phrom” Sopia announced proudly.

If Angkor Wat is remarkable for its vista, the Bayon for its riveting spirituality, then Ta Phrom fascinates for the relentless aggression of the vegetation. The shrill singing of a kettle boiling, a distant alarm ringing, sounds of the cicada, remind me all too loudly that the jungle is all about, that I am in its midst and that it has encroached on to the territory of Ta Phrom. Once an orderly home to the routine and religion of some 70,000 people it is now overrun by the sprawling power of the jungle, an exhibition to the fecundity and myriad of plant life.

Bushes sprout eagerly from atop a turret, trees lean heavily against struggling walls, everywhere there are roots, touching the stone, tracing its outline, gripping, grasping, entwining the stone in a deadly embrace. Bulbous thick heavy roots lie languidly on a wall, others seek out every crevice, tentacles slowly spreading, suddenly bursting forth from the stone spilling it in a tumbled heap. This ruined temple, in mortal combat with the jungle for hundreds of years, is in its final death throes. My romanticism was fuelled by the spectacular nature of this temple and I felt like bursting out into song, ‘The King of the Swingers’, or drifting into the role of Dennis Hopper on the set of ‘Apocalypse Now’.

Visiting Ta Phrom we had the joy of the temple virtually to ourselves, of being able to lose ourselves in it without distraction, without disturbance. But for how much longer will this be the selfish pleasure of the modern Angkor pilgrim? Not long if the skeletal forms of hastily constructed hotels lining the airport road are anything to go by. Or if Thailand has its alleged way incorporating Angkor as a Thai tourist resort - flights to Angkor from Bangkok are already billed as domestic not international flights.

Then finally to Bakhan and a steep climb to join the other modern day pilgrims, come to worship, revel in the glory of the sun setting behind Angkor Wat. But tonight they were disappointed as the sun faded quietly, there being no blaze of glory and no photographs for the album.

*

There are a great many sites at Angkor apart from the most popular three that I have already mentioned, but unfortunately too many to describe in detail here and I will have to limit myself to short mentions. There is the sheer beauty of the carving at Banteay Srei. The carving is fine and delicate, precise and painstaking, and continually surprises me with its depth and the quality of detail. There is the wry smile of an elephant’s eye, or the hissing stare of a naga, all brought to life with elaborate and intricate detail. Not only does this temple reveal the sublime architecture of the Khmers and its Indian influences but also the vast size and area of Angkor. Banteay Srei is thirty-five kilometres away from Angkor Wat, a distance over dusty, bumpy roads that is uncomfortable for the most devout of modern day pilgrims and must have been a major feat of travel across thick jungle for the thirteenth century devotee.

On the other hand there is Ta Keo, more simplistic in its construction, lacking the decoration and ornamentation of the other temples. Its simplicity causes me to wonder how all these colossal monuments were built. There is much speculation but it is likely that the stone was quarried some distance away at Koten and then transported to the various sites by elephant. Two pairs of lifting holes were drilled into the side of the stone, into which bamboo wedges were driven. When swollen with water these wedges would grip tightly allowing them to be lifted by elephants and floated down river. At the other end they were lifted off by elephants and then dragged up ramps by elephant and then raised into position by block and tackle. An impressive feat of engineering.

Preah Khan, ‘sacred sword’, is one of the largest-scale temples, a great many people. Priests of the sanctuary, servants and dancers having lived there. Nowadays the shoulder hugging corridors bear no signs of monastic life only the smell of damp and the dark. Lichen and moss have moved in, the jungle soon to be the next inhabitant of this temple. Stumbling and stepping over broken doorways and uneven paving stones, I headed to the dim light at the end of the gloomy corridor. The further away from the central complex the cooler it became and the more isolated and vulnerable I felt. Then suddenly at the end of the corridor I emerged into the harsh light of outside and was struck by the chorus of the jungle and swamped by undergrowth. A chill of unease ran down my spine and I turned hurriedly and retreated up the dank corridor, fleeing the encroaching jungle.

Returning to Angkor Wat did not disappoint as I discovered different subtleties and nuances. The bas-reliefs, an inch from the wall, seem to have an extra dimension to their epic struggles. The reflections on the walls and labyrinthine interior spaces are transformed by the light. An obese American waddled past causing a beggar to smile in amusement, to point in disbelief. Postcards were shoved in my face. Tourists try to thwart persistent peddlers with cries of “No, No.” An English traveller shoves away a Khmer boy, jibing “Easy China, can’t you see I’m trying to roll a joint.” And still such scenes cannot break the aura of Angkor. Individually the monuments of Angkor stand tall, together, as a whole they are truly spectacular.

*

Back in Phnom Penh we travelled from NGO to NGO, trying to glean information about the situation in the countryside, especially around Stung Treng and the Laotian border where we were headed tomorrow. Medicins Sans Frontières seemed positive, UNDP trod a more cautious path, and others had little to offer. This is the dilemma of Cambodia where a suspicion of the past still lingers. Information is uncertain, sometimes unreliable and usually contradictory.

Last year a bomb found in Phnom Penh was detonated in a controlled explosion. However there was a breakdown in communication and the city was not properly warned. Hence when the bomb was detonated everyone, fearing the worst, fled the streets, barricading themselves in at home or taking to the countryside. Despite many government announcements after the event that there was nothing to worry about, there was a virtual state of panic. This sad incident illustrates all too clearly the state of paranoid that the people of Phnom Penh still live in. Uncertainty and doubt still terrorises their subconscious. Another illustration of this doubt is that Cambodians do not invest in bulky material possessions that they cannot take with them should they have to leave in a hurry. Those who buy items such as furniture so are chastised for being foolish. Their money is used to buy gold which can be taken with them should the nightmare scenario become reality once again.

Yet despite such fears that are so entrenched and inherent it is difficult to see an end to them, the people are becoming more vocal and confident of voicing their opinions, less fearful of retribution for their outspokenness. Shortly after the elections in 1998 there was a peaceful demonstration by many whom felt that the election had not been fair, despite the assurances of UN officials. This was an expression of feeling that many had been too afraid to voice in the past and the fact that they were able to do so shows how far the country has come.

Before coming to Cambodia my impression was of a lawless country, but being there I did not feel threatened nor was I unduly worried about the people. I was wary of walking too far off the beaten track for fear of landmines, but did not fear for my personal safety on the streets. One day I left my unlocked bicycle under the guard of a policeman on the street and when I came back it was still there. A feat that I am unlikely to be able to repeat in many countries around the world. And yet there are reports kept by the various NGOs that detail the violence done to foreigners. A roadblock at which police, armed to the teeth, barking at nervous drivers and searching for illegal arms and weapons, is a small reminder of the underlying tension, the volatility of the country.

*

Despite a lack of good information about what lay ahead, we headed north to Kratie by boat. The boat that took us was similar to the one that deafened us en route to Srim Reap. The noise was the same, the same unsteady wooden boards and rickety gangplank, but the cargo and passengers were very different. The boat to Srim Reap was full of tourists and hardened backpackers, full of cameras and Walkmans, whereas the boat to Kratie had Ian and I as its only foreigners. If the boat to Srim Reap was full, the boat to Kratie was packed. Stacks of wool, electrical goods, scooters, heavy crates, a propeller shaft and food supplies were all sandwiched together. People pressed for space, cramped and cross-legged. Gone was the silence of the tourists appreciating the atmosphere, instead the excitement and chatter of going home or of going to visit family.

The journey itself was also different. The boat to Srim Reap is non-stop, whilst the boat to Kratie is a boat of everyday life, stopping to load and unload goods and passengers. Each stop entailed movement as we were forced to get out of the way of those disembarking, by those burdened with impossibly heavy loads. Vendors swarmed at piers of floating bamboo, pirogues attached themselves to the side of the boat in the hope of a sale. Eggs, sticky rice, bananas and plastic bags of Coca-Cola (the bottle is too precious to give away) were all on display. The tangy smell of dried fish filled our nostrils. Then without warning we were off again. Those who were too persistent in their sales-pitch screamed at the boat to stop, but it was too late and they resigned themselves to an enforced trip upstream. It was survival of the quickest.

An argument broke out and again I wished that I could speak the language and understand what they were saying. At the very least I was sure that they were using words that did not appear in my phrase book. The officious self-appointed ticket collector was disgruntled and tried to induce a loss of faith in the accused, who could not find his ticket. I sided with the accused, believing the collector to be incompetent – he had asked Ian and I for our tickets at least five times, and yet we were the only foreigners on the boat.

I returned to my book to find that a middle-aged man staring in fascination at the alien script. I handed him the book, he flicked unknowingly through the pages and returned it with a grateful smile. I resumed reading to find his head resting on my shoulder as he watched the pages, watching me turning the pages. A young teenager then moved next to me, obviously wanting to practise his English. He shuffled his legs in awkward silence as he tried to get my attention, sighing with impatience at my lack of response. At last it became too much and he broke the ice, “Where do you come from.” We then began a polite stilted conversation that was watched with interest by the middle-aged man impressed by the boy’s mastery of English and his ability to communicate with me.

Kratie is the last frontier of these express boats, indeed any large boats, as a large meandering bend and the shallows upstream prevent further passage. We arrived to find a one-strip town and an esplanade lined with palm trees and two hotels. One of the hotels had seen better days and was beyond hope; the other had just been opened, despite a lack of fittings, and was hoping for custom. Despite its unfinished newness, the awful plastic pink curtains, The Seap hotel would more than suffice for our meagre needs as we went off in search about news on the road to the border.

“The road is deemed safe though there is the threat of banditry. You never know what may happen. It’s been fine for a week.”

“What happened a week ago?”

"Four people were killed.”

“Tourists?”

“No, they were Khmer locals. You don't get many tourists here.”

“What would happen to tourists.”

“You guys would be different for them. A big problem.”

What kind of a problem? The mind races with possibilities. Of course any advice that we would be given was going to be blunt and matter of fact - if we travelled on the advice of someone and something were to happen to us they might think that they were to blame and in some way responsible. What is more if something were to happen to two tourists it might well become a major issue, making things difficult for those working out here. It was an awkward question and the answers that we received reflected that.

Alone together, Ian and I tried to assess the

risk. “What do you

think?” It was a difficult choice. We both desperately wanted to

continue as far north as we could, but the success of the trip was not

dependent on us reaching Stung Treng. We knew that we could not cross

the border at Stung Treng as it was closed and would have to come straight

back. “It would be foolish to risk everything for the sake of a

hundred kilometres or so - foolhardy to throw caution to the wind.” We

reluctantly decided that discretion would be the better part of valour

and opted to return to Phnom Penh and in doing so saved a couple of days.

|

|

|