“Lost, I stopped a man in the street and asked, “Excuse me can you tell me where the Hippodrome is?”

“Why? Who are you going to see?” was his bemused reply that was more a reflection on the lack of visitors to the area rather than of Lebanese sense of humour. There were obviously so few tourists to Tyre that he found it difficult to comprehend that anyone would come to see the Hippodrome, despite the fact that in its heyday it was the largest in the Roman world.

Had this been anywhere else in the Mediterranean I would have had little trouble in finding my way to the Hippodrome: there would have been signs, souvenir stalls, queues of coaches and all the trappings of tourism. But this is Lebanon. Once considered the Paris of the East, Lebanon fell off the tourist map when it disintegrated into civil war in 1975 and since then has been blighted by civil war and still lives under the shadow of unease and uncertainty on its southern border with Israel.

The saddest most visible scar from the war is the proliferation of high-rise, cheap, ugly apartment blocks that were built with little or no acknowledgement of planning permission. Modern day architects have neglected the good taste of their forebears, preferring to build in concrete. Our guide Philippe had in fact a qualified architect but as he is an architect with a conscience, something of a misfit in Lebanese architectural circles, work has been few and far between and he has had to supplement his income by guiding.

The physical evidence of the war was everywhere, bombed out buildings, broken roads and road blocks: the psychological legacy is locked away somewhere altogether less visible. Notwithstanding this past and the collective madness that blasted bullets and mortars from every corner, the people of Lebanon are charming, friendly and hospitable. In fact the country’s greatest asset is it’s people – having few of the resources of other Arab states, with the exception of water, the people have had to be enterprising, resourceful and above all welcoming to visitors.

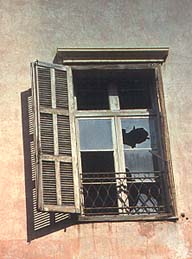

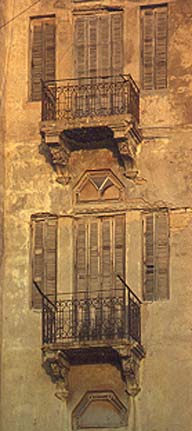

Situated on a natural crossroads, Lebanon has been conquered too many times to have any distinct ethnic unity. 95% of the population is classified as Arab, this is a linguistic and cultural definition rather than an ethnic one. Thus, Beirut, a microcosm of the country as a whole, is a tapestry of humanity inextricably woven together by threads of history. Located in the middle of Lebanon’s Mediterranean coast, it is a city of contrast: beautiful architecture is crowded out by concrete eyesores, traditional homes with gardens are dwarfed by high-rise buildings, smart top of the range cars vie for right of way with battered wrecks. Balconies, balustrades and bullet holes would be my overwhelming memory of Beirut architecture.

And of course the traffic - the roads are hopelessly congested: there are 1.5 million cars and only 4 million people (40% of whom are under 15 and thus cannot drive, in theory). In Lebanon the car is king and other forms of transportation such as walking or cycling are not even considered. The only other country with such a highly developed car culture is the United States. The Lebanese love their cars and there are basically two types of car: the new very fast car imported from Europe, still bearing its badges of nationality, and the decrepit car that is barely good enough for scrap let alone roadworthy. It is a measure of the country’s obsession with style and money that even poor people drive Mercedes albeit ones that have seen better days.

However for the unsuspecting tourist the experience of driving in Lebanon is either your idea of heaven or hell. The Lebanese are frustrated rally car drivers. A Lebanese driver without a horn is like a gladiator in the Circus Maximus without a trident. The rules of the road are simple: there aren’t any. There are no known speed limits, nothing to stop you overtaking on the wrong side and only a complete novice would bother to indicate before turning.

Away from the roads life in Lebanon is altogether more civilised. The shops and boutiques are chic and smart, emulating the fashions of Paris and Milan. Their cuisine is a refined inexpensive delight. Using fresh and flavoursome ingredients the Lebanese have taken the best aspects of Turksih and Arabic cooking and given them a French spin. A typical meal consists of a few mezze dishes, such as spinach pies, dips, dried cheese, pizza and stuffed vine leaves. This is followed by a main dish of meat (usually mutton) or fish, often stuffed with rice and nuts, plus a salad such as tabouleh or fattoush. The national dish is kibbeh, a finely minced paste of lamb and bulgur wheat, sometimes served raw, but more often fried or baked into a pie. Meals are often accompanied with araq, which is taken in a small glass that is replaced between each course. Although the reason for changing glasses is so that the taste of one dish does not remain in the glass and affect your palate, I found it a useful means of keeping a check on how many glasses I had drunk – very necessary when drinking araq.

But to classify all of Beirut as chic and smart is to oversimplify the issue. Part of the joy of Beirut, indeed Lebanon as a whole, is that it is difficult to pigeon-hole and assign labels. It is a mélange, a melting pot of cultures. Just when you think you are coming to terms with the culture, the city or the country, something emerges to challenge the norm and upset all your preconceptions. For instance whilst stuck in traffic I noticed a billboard advertising a cigarette brand that proclaimed ‘Expand your mind’. I was unsure what it meant and was unaware that the Lebanon had such a liberal drug policy. Whatever I decided to heed its advice and head out of Beirut and into the countryside. Hence I ended up in Tyre.

When I eventually found the Hippodrome in Tyre I was disappointed to discover that little remained of it, the years, the elements (earthquake) and centuries of invaders having taken their toll. However enough remains to get a feel for its former glory. At the very least it now provides an impressive running track for modern day fitness fanatics, would-be Olympians dreaming of greatness, the roar of the crowds now replaced by the roar of the city’s traffic.

Next stop was Byblos and hoping to avoid the problems of getting lost and having to ask directions, I decided to take a taxi, believing this to be the easiest option. But what I did not know was that the Arabic speaking taxi drivers refer to Byblos by its Arabic name of Jbail and thus when I asked for Byblos I was merely dropped off at the local branch of the Byblos bank. Having eventually managed to surmount the potential pitfalls of language, the town was a highlight, a relaxing haven surrounded by ancient buildings that was just over an hour away from the chaos of the capital.

At first sight Jbail appeared to be a fishing village, but I had to remind myself that this was Lebanon, which meant that along with an almost complete dearth of tourists, there were the remains of nearly seventy centuries of history lying around. Let me just emphasise that was not a typo and you did read seventy and not seven. It is claimed that Jbail has been inhabited longer than any other town on earth and it seems that much of the world’s history has passed through the town. The histories and myths of this town have been recycled as effectively as the Roman columns used to build walls and the ancient sarcophagai that now hold geraniums.

The three Bronze Age temples, the Phoenician burial tombs, the Roman theatre and the Crusader Castle were almost too much to take in and I had to retire to a café in the old town to take stock of Jbail’s history. Lying between the port and the castle, the old city is still enclosed by its medieval walls, a tranquil backwater of natural alleys, stone houses, sweetly scented gardens and numerous miniscule churches. It was the perfect place to try and collect my thoughts and come to terms with the scale of Lebanon and it’s history.

Yet if I found it difficult to comprehend the history of Jbail, I was simply bowled over by the magnitude of Baalbek. Even hardened sceptics and temple weary tourists fall open-mouthed when confronted by the sheer size and scale of Baalbek. Only the mountains, which form the backdrop, can dwarf its enormous size.

Every school child knows that the Romans built big. But the temple at Baalbek is the ruin of the largest religious structure ever built by Rome. The base of the temple, begun around 20 AD, was almost 290 feet long and 160 feet wide. The 54 columns that supported the structure’s immense roof were each more than seven feet in diameter and soared 65 feet in height. There was quite simply nothing else like it in the whole Roman Empire. Six of the 54 great columns from the main temple still stand. Even in their miserably shrunken number, surrounded by ruins, they made me shiver thinking about the audacity of the Roman builders. The huge blocks are testament indeed to the pomp and power of Rome.

These wonders of the classical world remain as impressive ruins but more remarkable still is the gigantic stone podiums within which these structures stand. Incorporated into the outer wall are the three largest building blocks ever used in a man-made structure. Each one weighs an estimated 1,000 tonnes and even more extraordinary is that a quarter of a mile away in a limestone quarry is an even bigger building block at an estimated 1,200 tonnes. The enigma is that there is not a crane today that can even think of lifting a 1,000 tonne weight never mind a 1,200 weight like the stone block left in the quarry. Confounding the mystery further, the builders managed to position these stones side by side with such precision that according to some, not even a needle can be inserted between them.

In the fading afternoon light we left Baalbek to visit the Ummayid site of Aanjar. Laid out in a rectangular plan and surrounded by hefty fortification walls, Aanjar is perfectly symmetrical, divided into four equal quarters by two main avenues, which meet in the middle of the town to form crossroads. However it was not the symmetry but rather the special beauty of Aanjar that struck me. The city’s slender columns and fragile arches stand in contrast to the imperial majesty and massive bulk of Baalbek. It was delicate and charming and the twittering of birds with the snow capped mountains in the background combined to make it tranquil.

But nothing in Lebanon is quite what it seems and as we wandered around the site we discovered that some of the houses towards the back of the site were occupied by Syrians. Rumours suggest that they are secret police. Whether or not that is the case, Syrians are on Lebanese soil and the Lebanese seem able to do little about it – the latest in a long line of conquerors and occupiers of this land.

It is a land that fires your imagination and appetite to know about

its past, and I felt that I had discovered and learned a huge amount

about Lebanon in my short stay. But it would be arrogant to suggest that

I understood or knew the country, having just scratched the surface.

But it is a scratch that will not go away and one that I will continue

to itch.

|

|

|