The Magic of Mali

“Where are you going to?”

“Mali.”

“Bali?”

“No, Mali. West Africa.” A blank look reveals all too clearly that my interrogator has no idea where Mali is. I try to be more helpful:

“Timbuktu is in Mali”

“Oh” is the hollow response, revealing that Timbuktu has lost its former allure and charm and that today we are no better off than those in the early eighteenth century as to Timbuktu’s exact location. It was in the early eighteenth century that the race to locate Timbuktu began – in 1824 the Royal Geographical Society of Paris offered a prize of 10,000 French Francs for the first explorer to return with a verifiable account of the city. They were attracted by legends of the mysterious beauty of Timbuktu and, more specifically, by tales of its vast fortune.

Today, the magnificent wealth of earlier African empires has disappeared leaving the modern state of Mali and one of the poorest countries in the world today. There is little evidence of modernisation in the dusty capital of Bamako yet the pace is far from sedate. The city centre is cluttered with roadside stalls, music blasting from doorways. There is a buzz to the city and the people are busy but not so busy that they ignore each other. Smiles and greetings are the refreshing norm.

Moving out of Bamako in a north-easterly direction, I came to the small brick town of Djenne that like Timbuktu had seen better days. Djenne’s heyday was in the fourteenth century under the Malian Empire and in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries under the Songhai empire, but today it is a sleepy town that bursts into life once a week on market day on Mondays. Djenne is famous for its Grand Mosque built in 1905 in traditional Sudanese style architecture, which is said to be the highest mud brick building in the world. Physically little has changed over the centuries and Djenne is unquestionably picturesque. The Djenne market had a bewildering range of items for sale but the real attraction was the blaze of colour against the backdrop of the famous, imposing mosque.The local policeman thought that Djenne and its mosque so famous that I would want a ‘Djenne’ stamp in my passport.

The journey from Djenne to Mopti was a rough three hours by road but a far more interesting journey and much smoother is a day’s journey in a pinasse. A pinasse is a larger version of a pirogue, a dug-out which is some thirty foot long by six feet wide with a small outboard engine. The pinasse glided along the Bani along the Bani, one of the largest tributaries of the Niger, and the Niger, the outstanding geographical of Mali and the third largest river in Africa. I dreamily imagined myself to be an early explorer but I hasten to add that I did not adopt the policy of the eighteenth century explorer Mungo Park, which was to shoot all the natives he encountered.

Rather I welcomed all contact with these remarkably friendly people. Poor beyond our narrow western conception they were proud, laughter-filled and disturbingly beautiful .Yet my diplomacy did not extend to handing out pens and sweets much to the disappointment of the expectant children. Their incessant cries of “un cadeau, un cadeau” being one of the more ugly faces that tourism and such intimate contact with villages along the river has wrought.

Mopti has become the country’s major river port where commerce pulls together all the peoples of Mali – Bambara, Bozo, Fulani, Dogon and Turaeg to name a few. Mali might be poor in economic terms but it more than makes up for this with its cultural diversity and richness. Mopti has a mosque similar to the one in Djenne but here the attraction is not the mosque but the harbour. The harbour is the hub, the melting pot: large wooden pinasses laden with their various cargoes are moored, flags fluttering; Fulani women, dressed in colourful garb and heavy gold jewellery, sell and barter dried fish; Tuaregs, the illustrious warriors of the blue veil, have temporarily deserted their desert lifestyles in the north to sell their salt. Salt was once the basis of trans-Saharan trade and was traded pound for pound with gold.

Mopti was a wonderful assortment of sights, sounds and smells, a real sensory assault. By late morning it was almost too much to take in in one day and I was in dire need of refreshment and a chance to collect my thoughts. Bar Bozo was just the place. Here not only was I able to enoy capitaine (Niger perch) and obtain liquid refreshment but also spend a languid afternoon indulging in people watching. There can be few better past-times than watching the world go by and no place less fascinating than Mopti harbour. Located in one corner of the harbour it was ideal for watching pirogues ferry people to and from their villages, the colourfully dressed women doing their washing in the not so colourful river, Bozo fishermen building a pinasse and the manufacture of nails out of rusty scraps of metal.

But for me the highlight of my time in Mali was the four days I spent walking in Dogon Country. The main area of Dogon country is the two hundred kilometre Bandiagara escarpment, known locally as the falaises. It is thought that the Dogon people migrated to the falaises to enjoy the natural protection that they afford - in places they rise to a sheer thousand feet – and hence managed to preserve their traditional religion in the face of Muslim expansionism. To this day the falaises have protected the Dogon culture and its complex and intricate system of animist beliefs.

The predecessors of the Dogon, the Tellem, were a mysterious people who built houses on the rocks of cliff faces and buried their dead in caves above these houses.

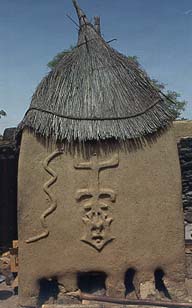

Walking through the falaises and entering Dogon villages, I was struck byt the huge amount of symbolism that exists in Dogon culture. The shape and the layout of the village has symbolic importance. The village is laid out in the shape of a human body, the smithy (blacksmith) represents the head, shrines at the opposite end the feet, the group of houses in the centre the chest, and the con-shaped shrine in the centre the sex organ. The ginna or family home has similar symbolic meaning and it too is built in the shape of a human form. On various buildings, especially granaries, are elaborate patterns depicting scenes from the Dogon creation and mythology. Perhaps most symbolic of all is the Dogon door on which Dogon tradition and mythology is summarised. On the door, shadowy figures enact scenes from the creation, from the arrival in the Bandiagara region and represent the eight original Dogon ancestors.

The most dramatic manifestation of such symbolism is the Mask Dances, which are performed at celebration and funerals. Dogon masks are prized and sought after by collectors of African Art but they were not meant to be viewed simply as sculptures and are difficult to appreciate when taken out of context. In the Dogon village of Tirelli a Mask Dance was performed for our benefit. It smacked of commercialism but it was enthralling. The sound and motion brought the masks to life with dramatic and disturbing effect. It was a moving experience and even if the dance itself was only a performance it gave the masks so much more meaning and potency than viewing them in the sterile environment of a museum.

At the edge of each village, millet was pounded in wooden mortars. The high staff-like pestles were wielded with resounding thuds by women whose confident muscular elegance poured scorn on western concepts of femininity.

Walking through Dogon country is a hazardous business for the sole reason that there are many areas, such as shrines, fetishes and divination tables that are off limits. A guide is indispensable not only for unravelling the complexities of the Dogon civilisation but also for directing you where you could or could not walk. Our guide, Hammah, introduced us to the Hogon in the small village of Arou. The Hogon is the spiritual leader and the only person with an accurate and deep knowledge of Dogon art and rituals. The other important introduction that Hammah mad e was introducing us to Konjo, millet beer. Not put off by rumours that it gave you flatulence, I first poured some on the ground for and in memory of my ancestors than sampled my mug. It tasted not unlike a friend’s poor attempt at home brew. It was however drinkable and I did not want to lose face for a good Dogon is a Dogon who likes his beer.

On our last night in Dogon country we feasted

on Mechoui, whole roast lamb cooked over a spit. A suitable way to

round off a truly enlightening

and inspiring visit to West Africa. My only disappointment was that I

had not visited Timbuktu and in so doing satisfy a vain desire to be

able to say that ‘I have been to Timbuktu’. I consoled myself

with the words of René Caillié, a Frenchman who in 1828

was the first explorer to return from a visit to Timbuktu, “I found

it neither as big or as populous as I had expected. Everything was enveloped

in a great sadness. I was amazed by the lack of energy, by the inertia

that hung over the town.”

|

|

|