A Journey to the Source of the Mekong

The first hailstone landed to our right. We were both so incredulous at its size, its sudden unannounced arrival that we did not contemplate the obvious – that there would be more. We were quickly roused from our daze as all about us the ground began to ping with their arrival. A nearby stream was churning under the heavenly barrage, its water seemingly raked by gunfire. The size and the concentration of these hailstones was awe-inspiring, but all fascination was stung out of me when I was hit square and hard in the back, as if by a squash ball. This was the beginning of the end.

High on the remote Tibetan plateau, on a day that I shall never forget, we were to be thwarted in our attempt to follow the Mekong River from its mouth in Vietnam to its source. To reach this point Ian Gardener and I had cycled over 4,500km through four countries: Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and China. Yet just 150km short of our goal, we were to be defeated by the elements – thick cloying mud that made cycling impossible, hailstones that were frighteningly large and lightning that literally made our hair stand on end. The final straw was heavy snow.

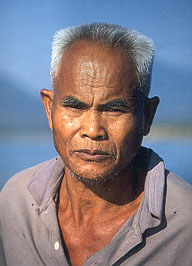

Our journey had begun four months previously in the labyrinthine network of the channels that make up the Mekong Delta. Far removed from the harsh, remote plains of Tibet, the delay teemed with activity. The floating markets were a riot of colour as heads bobbed up and down in the barter of heated exchange, small boats rushed to market and large barges thudded to unload their cargoes. Our progress was sedate and leisurely in this region of productivity and plenty, the toil of Tibet seeming many miles distant.

From Vietnam we followed the Mekong into Cambodia where travel is less easy and we had to be a little more cautious. Cambodia is a country that is not at ease with itself and is struggling to find an identity, seeking stability after so many years of toil and trauma. It is an uneasiness that is infectious, and we played safe by opting to travel by the relative security of boat rather than by the uncertainty of bicycle. However this did not prevent us from enjoying Cambodia, especially the wonders of Angkor Wat and the many surrounding temples. Individually the monuments of Angkor stand tall, together they are truly spectacular – there can be few sights in the world as awesome and overwhelming.

It was in southern Laos that our ordeal by bicycle began in earnest. We cycled along dusty footpaths that took us past canoes wallowing in the water and the delighted shrieks of naked children playing and splashing in the river. We passed sleepy villages and women wobbling under the burden of buckets of sloshing water. Amongst the bamboo and shade along the Mekong life was soporific, untouched and undoubtedly enchanting.

We tried to be as unobtrusive as possible, not wishing to disturb such tranquil scenes, but invariably our silent progress was noticed. Young toddlers fascinated by Ian cycling by would step out into the middle of the path only to get the fright of their life when I brought up the rear. A young girl grooming her mother’s hair got the shock of her life and uttered a startled cry as we whizzed silently past, only to burst into laughter, amused at her own surprise.

Unfortunately such scenes did not last long as the road deteriorated into a rutted, rocky hell. The constant jarring and juddering made cycling hell and numb bums very sensitive to hours spent in the saddle. Such conditions took their toll and Ian was in some discomfort as his left hand was reduced to a claw by tendonitis.

Throughout such times the Laotian people were an invaluable source of inspiration. As we passed through a village a child would inevitably spot us and a cry of greeting of “Sabaai dee” would rise like a siren call. Children shouting and waving ecstatically would run to the roadside, their infectious excitement whipping the whole village into a hysterical frenzy. But all the excitement abruptly came to an end when we stopped. The youngest would freeze in their tracks with fear, turn and run to the sanctuary of their homes and mothers, never having seen foreigners at such close range before.

Thankfully we did have some respite from the road, most notably the soporific charms of Luang Prabang, the ancient capital where time stands still and the past seems more alive than the present. A surreal cross between ‘Sleeping Beauty’ and the ‘King and I’, Luang Prabang epitomised the easy-going, laid back atmosphere of Laos. It was difficult not to be seduced by its bewitching attractions and stay for weeks, but we had to get back on the road or the river to be precise. There being no path or road that followed the river we had to progress north by cargo boat.

The boat was an experience in itself but most bizarre of all was the home-made fireworks display that we witnessed en route. We stopped at a large sandbank whilst the captain produced a bag of goodies: several smaller plastic bags, some string, numerous elastic bands, two fuses and two sticks of dynamite – his home-made explosives kit. Ian and I exchanged nervous looks as the captain put together his makeshift grenade. Satisfied with the end result, he nonchalantly lit the fuse with his cigarette and lobbed the grenade into the river. The resulting explosion brought a handful of tiny fish floating to the surface. Fish so small that any self-respecting angler would have thrown them back – but when you fish with a grenade, self-respect hardly comes in to the equation.

From Laos we cycled north into Yunnan, a province in the Southwest of China, where we were greeted by tarmac and traffic. The tarmac did not last but unfortunately the traffic did and we spent days covered in the dirt and dust of passing trucks. In China we also began to gain altitude and seemingly every other day we had another mountain pass to struggle over. Mao described China as the land of a hundred rivers and a thousand mountains” and after our experience in Yunnan I would not disagree with him.

But once again it was the reception and support that we got from the local people that we found so encouraging. Whenever we stopped I a village a crowd would inevitably gather. As we slurped our noodles, awkwardly trying to work our chopsticks in unison, we were watched and studied, our every movement scrutinised. They were amazed at the quantity of food that we would devour yet full of praise for the distance that we had cycled. In broken Chinese we would try to get an idea of what lay ahead but local knowledge was scanty and far from reliable. The oriental concept of a road differing from our occidental viewpoint, their understanding of direction and distance being far more vague than our own precise compass and odometer enhanced definition.

Yet despite difficulties with direction and deciphering Chinese maps, we made it to Tibet, the exotic and mysterious ‘Roof of the World’. In Tibet we travelled by stealth trying to avoid towns and contact with the authorities. Foreigners are only allowed to travel recognised routes in Tibet or with guides and official permission, and two cyclists following the Mekong did not qualify on either count. However the authorities – though we were to fall foul of them on a couple of occasions – were the least of our worries. Our greatest challenge was the physical demands of cycling at an altitude of over 13,000 feet (4,200m). The altitude and the lack of oxygen caused a shortness of breath but it was the continued exposure to the elements, especially the relentless wind, that was most exhausting.

A passage from my diary brings home some of the pain. “And the rain came. Hard, driving, biting at exposed parts of the face, saturating waterproofs. My feet were sodden, toes squelching unpleasantly in soaking socks. The wet was uncomfortable, made me feel miserable and sapped my energy, but what disheartened me most was the fact that with my cagoule done tightly up my vision was limited, almost non-existent. There is little more disconcerting then being able to see a couple of feet ahead in driving rain, staring at muddy puddles, muddy road, puddles. The wind was bitterly cold. I was racked with shivers and my hands were painfully numb. But it was the fact that all I could see was the mud at my feet that I found to be most dispiriting.”

The landscape was vast, remote and sparsely populated and for much of the time we had to be self-sufficient, carrying our own freeze-dried food and filtering water from the streams. On several mornings we awoke to frost and to find that the water in our bottles had frozen overnight. Not only did we have to drink this icy cold glacial water but we had to wash and bathe in it – we might have believed ourselves to be hardy, to be able to endure the elements, but exposure to such low bathing temperatures prove otherwise.

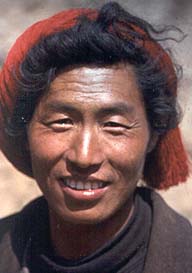

The only people that we came across were Tibetan nomads eking out a hardy existence on the exposed plain. They have little surplus and nothing in the way of comforts yet they are always happy to give. On a number of occasions we were invited into the gloomy warmth of their tents and presented with a cup of yak-butter tea. One memorable time it was not tea but a leg of raw, dried yak. Such generosity was commonplace, almost embarrassing.

The nomads were fascinated by our bicycles and by the distance that we had cycled. They were curious to know why rich westerners were not travelling by jeep – a question we often asked ourselves when faced with the vertiginous terrain. Our miniature bicycle pump was often the subject of heated debate, even to the extent that it was passed around so that everyone could feel its weight and examine it. The argument would only be resolved when one of us would pick up the pump, move to a bike and motion the pumping up of a tyre. This resulted in a nodding of heads and looks of ‘I told you so’.

One night we were getting into our sleeping bags when we were visited by the ‘Lone Ranger’ of the high plateau. More interested in our tent and equipment than herding his yaks up for the night, he noisily poked his head into the tent, his horse trying to follow suit. His horse, a grey, furthering the Lone Ranger metaphor, was ostentatiously dressed in red pom-poms, a measure of the man's status. The 'Lone Ranger' himself was a real character, thick heavy rimmed glasses as per Jiang Zemin that were incongruous with the outdoor cowboy image, faded denim jacket, battered hat and black shoes more suitable to an office than the Tibetan plateau, and a gleaming gold tooth straight out of a Serge Leone spaghetti western.

He was actually quite concerned for our welfare. Not believing that we would be warm enough, he asked the ubiquitous question, " Leng bu Leng?", "Are you not cold?" I believe that this is the only question that Tibetans think we can understand or perhaps the only phrase that they know in Chinese. His concern was touching, his invitation to come over and bed down at his ranch, i.e. nomadic tent, generous. Flattered by his invitation, we politely declined and still smiling he galloped off into the distance.

We awoke the next morning to find everything covered in a thick layer of snow. Undaunted, being so near yet so far, we decided to battle doggedly on. The snow made the going soft and difficult, tyres got bogged down under our weight, our bikes and gear were soon covered in mud. We struggled up a pass of 16,000 feet. If the altitude was not bad enough, the lack of oxygen causing a shortness of breath, the gradient of the slope and its gruelling surface of loose stone, defeated us, and often we were forced to dismount and struggle uphill, pushing our bikes.

"Never again, " Ian muttered to himself as we reached the top, collapsing to the ground only able to exchange wry looks. The spectacular views afforded us by the summit only just compensated for the physical hardship of the ascent. However the summit not only revealed a stunning array of snow capped peaks that stretched as far as the eye could see, but also that the heavens were conspiring to thwart our attempt to reach the source: the skies above were dangerously dark, an ominous blackness, that filled us with dread.

"What have we done to upset the Gods?" we thought to ourselves, as the unsettling rumblings that charged the skies overhead erupted in a ferocious downpour of hailstones. Not just ordinary hailstones, but hailstones that were the size of table tennis balls, hailstones that hurt and that made us feel insignificant, like little boys out of their depth.

In the bleakness of the wilderness that is Tibet, our limitations had

been harshly exposed by the elements, which were simply too much for

us. Undoubtedly it was disappointing to be defeated by adverse weather

conditions but at the same time turning back was not an easy decision,

it required a certain bravery. Whilst it was incredibly frustrating to

have come so far, to have the source of the Mekong, the aim and goal

of our trip, so tantalisingly within our reach and yet unable to make

it, our success was in coming as far as we had.

|

|

|